Michel Gourgues, The crucified one. From scandal to exaltation

(original title: Le crucifié. Du scandale à l’exaltation).

Montreal - Paris: Bellarmin - Desclée (Jésus et Jésus-Christ, 38), 1988, 178 p.

(Detailed summary)

Michel Gourgues, of the Order of Preachers Friars, is a full professor in the Faculty of Theology at the Dominican University College in Ottawa, Canada, and is responsible for courses on the New Testament. Born on August 22, 1942, he entered the Dominicans in 1963, made religious profession on August 4, 1964, and was ordained priest on May 30, 1970. After completing his studies in philosophy and theology at the Dominican University College in Ottawa, he obtained his Ph.D. in 1976 at the Institut Catholique de Paris ("Le Seigneur a dit à Mon Seigneur..." L'application christologique du Psaume 110:1 dans le Nouveau Testament). He is also a tenured student at the French Biblical and Archaeological School in Jerusalem. Michel Gourgues is the author of numerous publications. These include:

- A la droite de Dieu. Résurrection de Jésus et actualisation du Psaume 110:1 dans le Nouveau Testament (At the right hand of God. Jesus' resurrection and updating of Psalm 110:1 in the New Testament). Paris : Gabalda (Études Bibliques), 1978.

- Les psaumes et Jésus — Jésus et les psaumes (The Psalms and Jesus - Jesus and the Psalms), Cahiers Évangile no 25. Paris : Cerf, 1978.

- Jésus devant sa passion et sa mort (Jesus before his passion and death), Cahiers Évangile no 30. Paris : Cerf, 1979.

- L’an prochain à Jérusalem. Approche concrète de l’espérance biblique (Next year in Jerusalem. Concrete approach to biblical hope), La Vie Spirituelle 639. Paris : Cerf, 1980.

- L’au-delà dans le Nouveau Testament (The afterlife in the New Testament), Cahiers Evangile no 41. Paris : Cerf, 1982.

- « Pour que vous croyiez... » Pistes d’exploration de l’évangile de Jean ("For you to believe... " Paths to explore the Gospel of John). Paris : Cerf, 1982.

- "L'Apocalypse" ou "les trois Apocalypses" de Jean? ("The Apocalypse" or John's "Three Apocalypses"?), 1983, 26 p.

- Le défi de la fidélité — L’expérience de Jésus (The Challenge of Faithfulness - The Experience of Jesus). Paris : Cerf (Lire la Bible, 70), 1985.

- (Collaboration) À cause de l’Évangile (For the sake of the Gospel). Études sur les Synoptiques et les Actes offertes au Père Jacques Dupont, o.s.b., à l’occasion de son soixante-dixième anniversaire. Paris : Cerf (Lectio Divina, 123), 1985.

- (Collaboration) L’Altérité. Vivre ensemble différents (Otherness. Living together different). Actes d’un colloque pluridisciplinaire pour le 75e anniversaire du collège dominicain de philosophie et théologie, Ottawa, 4-6 oct. 1984. Paris-Montréal : Cerf-Bellarmin (Recherches, 7), 1986.

- Mission et communauté (Actes des Apôtres 1-12) (Mission and community), Cahiers Evangile no 60. Paris : Cerf, 1988.

- Le Crucifié. Du scandale à l’exaltation (The Crucified One. From scandal to exaltation). Montréal- Paris : Bellarmin-Desclée (Jésus et Jésus-Christ, 38), 1988

- L’Évangile chez les païens (Actes des Apôtres 13-28) (The Gospel among the Gentiles ), Cahiers Évangile no 67. Paris : Cerf, 1989.

- Prier les hymnes du Nouveau Testament (Praying New Testament hymns), Cahiers Évangile no 80. Paris : Cerf, 1992.

- Jean, de l’exégèse à la prédication I (John, from exegesis to preaching I). Carême et Pâques Année A. Paris : Cerf (Lire la Bible, 97), 1993.

- Jean, de l’exégèse à la prédication II (John, from exegesis to preaching II). Carême et Pâques Année B. Paris : Cerf (Lire la Bible, 100), 1993.

- Luc, de l’exégèse à la prédication (Luke, from exegesis to preaching). Carême et Pâques Année C. Paris : Cerf (Lire la Bible, 103), 1994.

- Foi, bonheur et sens de la vie: Relire aujourd’hui les Béatitudes (Faith, Happiness and Meaning of Life: Rereading the Beatitudes Today). Montréal : Mediaspaul, 1995, 102 p.

- Cinquante ans de recherche johannique. De Bultmann à la narratologie (Fifty years of Johannine research. From Bultmann to narratology), dans « De bien des manières ». La recherche biblique aux abords du XXIe siècle. Actes du Cinquantenaire de l’ACEBAC (1943-1993) édités par Michel Gourgues et Léo Laberge. Paris : Cerf (Lectio Divina, 163), 1996.

- Préface à l’ouvrage Les Patriarches et l’histoire. Autour d’un article inédit du père M.-J. Lagrange, o.p. (Patriarchs and history. Based on an unpublished article by Father M.-J. Lagrange, o.p.) Paris : Cerf (Lectio Divina), 1998

- La vie et la mort de Jésus. Une même dynamique (The life and death of Jesus. The same dynamic), dans Mourir, Christus 184. Paris : IHS, 1999.

- Les paraboles de Jésus chez Marc et Matthieu - D’amont en aval (The Parables of Jesus in Mark and Matthew - From Upstream to Downstream). Montréal : Médiaspaul, 1999.

- Jean-Marie Tillard, o.p. (1927-2000), La Vie Spirituelle 738. Paris : Cerf, 2001.

- Le Pater. Parole sur Dieu. Parole sur nous (The Father. Word about God. Word about us). Namur : Lumen Vitae (Connaître la Bible, 26) 2002, 75 p.

- Jésus et son père (Jesus and his father), dans La paternité pour tenir debout, Christus 202. Paris : IHS, 2004.

- Partout où tu iras... : Conceptions et expériences bibliques de l’espace (Wherever you go... : Biblical Conceptions and Experiences of Space), en collaboration avec Michel Talbot. Montréal : Médiaspaul, 2005.

- En ce temps-là... (In those days...), en collaboration avec Michel Talbot. Montréal : Médiaspaul, 2005.

- En esprit et en vérité. Pistes d’exploration de l’évangile de Jean (In spirit and in truth. Paths of exploration of the Gospel of John). Montréal : Médiaspaul, 2005.

- « Laisse donc voir ! » [Matthieu 5, 3-16] ("Let me see!" [Matthew 5:3-16]), La Vie Spirituelle 763. Paris : Cerf, 2006.

- Serviteurs du Christ à la naissance de l’Église (Servants of Christ at the birth of the Church). Paris : Cerf (Biblia, 64), 2007.

- Marc et Luc : trois livres, un Évangile : Repères pour la lecture (Mark and Luke: Three Books, One Gospel: Landmarks for Reading). Montréal : Médiaspaul, 2007.

- Les deux lettres à Timothée. La lettre à Tite (The two letters to Timothy. The letter to Titus). Paris : Cerf (Commentaire biblique : Nouveau Testament, 14), 2009.

- « Souviens-toi de Jésus Christ » (2 Tm 2,8.11-13) : De l’instruction aux baptisés à l’encouragement aux missionnaires ("Remember Jesus Christ" (2 Tim 2:8.11-13): From instruction to the baptized to support to missionaries), dans Les Hymnes du Nouveau Testament et leurs fonctions. Paris : Cerf (Lectio Divina, 225), 2009.

- « Croce », dans G. RAVASI, R. PENNA, G. PEREGO (ed.), Dizionario dei Temi Teologici della Bibbia. Balsamo: Edizioni San Paolo, 2010, pp. 254-262.

- Le crucifié (The Crucified One). Paris: Mame-Desclée, 2010, 200 p.

- Je le ressusciterai au dernier jour : la singularité de l’espérance chrétienne (I will resurrect him on the last day: the singularity of Christian hope). Paris : Cerf (Lire la Bible, 173), 2012

- Les pouvoirs en voie d’institutionnalisation dans les épîtres pastorales (Powers in the process of being institutionalized in pastoral epistles), dans Le Pouvoir — Enquêtes dans l’un et l’autre Testament. Paris : Cerf (Lectio Divina, 248), 2012.

- Ni homme ni femme : l’attitude du premier christianisme à l’égard de la femme : évolutions et régressions (Neither man nor woman: the attitude of the first Christianity towards women: evolutions and regressions). Paris-Montréal : Cerf-Médiaspaul (Lire la Bible), 2013

- Les formes prélittéraires, ou l’Évangile avant l’Écriture (Preliterary forms, or the Gospel before Scripture), dans Histoire de la littérature grecque chrétienne, 2. De Paul apôtre à Irénée de Lyon. Paris : Cerf (Initiations aux Pères de l’Église, 2013.

- Plus tard tu comprendras. La formation du Nouveau Testament (Later you'll understand. The formation of the New Testament). Paris-Montréal : Cerf-Mediaspaul (Lire la Bible, 196), 2019, 187 p.

The crucified one. From scandal to exaltation.

Summary

Most historians agree that the crucifixion of Jesus in Jerusalem, outside the city gate, was at nine o'clock in the morning on a Friday, the Sabbath eve and day of preparation for the Jewish Passover, April 7, 30 AD. It is a shock to his disciples. It should be noted that in the Roman world, this method of execution was reserved only for criminal slaves. In the Jewish world, such a death meant that the person was cursed by God. The feeling of failure and the disillusioned reaction of those who followed him is echoed in the account of the disciples of Emmaus, composed several years later (Luke 24: 20). But an unexpected event changes everything, as the disciples of Emmaus also testify: Jesus has risen from the dead, he has appeared to Simon. From that moment on, a long reflection begins, using the Bible to understand this absurd and unacceptable death.

But it is easy to imagine how difficult it was for the first Christians to speak publicly about this death on the cross before Jews for whom it is totally scandalous, and before Greeks for whom it is pure madness. Also, in the texts that refer to the oldest traditions, there is a great discretion and a certain silence about the way Jesus died, emphasizing rather the resurrection. This is the case of the hymn found in the Letter to the Philippians (2: 8) where Christ is presented as the one who emptied himself of his divine condition and humbled himself to the point of obeying unto death, or of the ancient creed quoted by Paul in his epistle to the Corinthians (15) which is content to speak of a death for sins and a resurrection on the third day. Even the evangelists show great discretion and sobriety when mentioning the cross and only really address the subject when it is impossible to avoid it, at the time of Jesus' crucifixion. But they insist on his innocence supported by Pilate himself. Above all, they try to draw parallels with certain passages of Scripture, especially the Psalms, to show that this was part of God's plan. It was St. Paul who first dared to tackle this subject head on by making the cross the center of his preaching, as we can see in the First Epistle to the Corinthians. For him, this is how God wanted to offer his salvation, thus manifesting his power and wisdom through what appears to the world as weakness and foolishness. He goes even further. If the Law considered the crucified as cursed, and yet God raised the crucified Jesus, it is because the Law is useless for salvation and, on the contrary, only faith in Jesus saves.

In the meantime, Christian reflection continues on all these events. It seems that it is first of all the fourth song of the Servant of Yahweh in the prophet Isaiah (...a man despised and discredited. He bears our sins and suffers for us...; see Is 53: 2-5) which helps the first communities to find meaning in this ignominious death. Since we are in a Jewish setting, the ritual related to the temple will also offer some analogies. First of all, there is the sacrifice of animals offered for the forgiveness of sins: did not Christ shed his blood in the same way? Except that in his case, it is once and for all: a permanent forgiveness. There is also the annual ritual of the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur) where the blood sprinkled on the altar expressed the forgiveness offered to all the people. This is how the idea of a bloody death in our favour for the forgiveness of sins developed. This reflection will also take a parenetic turn: Christ, faithful to God's will, endured the trials of life until he accepted this atrocious death and became the model of the believer. But there is more. The believer who suffers because of his commitment to the service of the Gospel, participates in the cross of Christ.

Note: The following is a summary of the book.

Table of Contents

Introduction. Why the cross? The ramifications of a question.

- The singular cross of Jesus: at the place called the Place of the Skull, at the third hour.

- The plural cross of believers: "I am crucified with Christ" (Gal 2: 19).

- Approach

Part one. The event. History and testimony

- The Cross in the Passion Narratives

- "Crucified under Pontius Pilate" - "This despicable mystery, full of shame"

Part two. From Failure to Fecundity - Progressive Development of a Theology of the Cross

- The cross as an unveiling about Jesus Christ and God

- The cross as an unveiling about ourselves

Part three. From the cross of Christ to the cross of Christians

Introduction. Why the cross? The ramifications of a question.

When we consult the dictionary, we note that after referring to the instrument of torture for those condemned to death in antiquity, consisting of two transverse pieces of wood, the definition of the word cross passes to the figurative sense: punishment, affliction, and especially trials that God sends to the Christian. But this figurative meaning only reopens the question: why does God send the cross?

- The singular cross of Jesus: at the place called the Place of the Skull, at the third hour

It is a unique experience located in Jerusalem, at the Golgotha or the place called the Skull, outside the city gate, at nine o'clock in the morning on a Friday, the Sabbath eve and day of preparation for the Jewish Passover, which historians place on 7 April in the year 30. Referring to this event, Paul speaks of scandal, not in the sense of being indignant, but in the strong biblical sense of a stumbling block or obstacle that causes one to lose faith or shatter one's worldview, and leaves the individual completely helpless.

- The initial shock: "And we were hoping..."

He (Jesus) asked them (the disciples of Emmaus), "What things?" They replied, "The things about Jesus of Nazareth, who was a prophet mighty in deed and word before God and all the people, and how our chief priests and leaders handed him over to be condemned to death and crucified him. But we had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel. Yes, and besides all this, it is now the third day since these things took place. (Lk 24: 19-21)

For the disciples of Emmaus, the death of Jesus, and more particularly his death on the cross ("crucified him"), represented a scandal, which caused them to stumble in their hope, marking the end of the immense trust placed in the prophet of Nazareth. We must first take the time to understand all the shocking character of the cross before moving on to the meaning brought by faith in the resurrection, as Cyril of Jerusalem (314-386) will do when he says: "But since the cross was followed by the resurrection, I can speak of it without blushing" (Catechetical Lectures, XIII, 4). Let us therefore try to retrace the journey of the communities, their progressive transition from the scandalous cross to the victorious cross.

- The shock overcome: "Nothing but Jesus Christ and Jesus Christ crucified"

While Paul tells the Corinthians that he did only want to know among them that Jesus Christ was crucified (1 Cor 2:2), the New Testament as a whole is much more timid on the cross: the verb stauroō (to crucify) and the noun stauros (cross) appear 46 and 27 times respectively. Now, two-thirds of all these uses are concentrated in the Gospel passion narratives where it is inevitable to speak of them, and among the 22 other uses that remain, 12 are found in the epistle to the Galatians and in the first two chapters of 1 Corinthians. There is, therefore, a great reserve with regard to these words. And when we look at the traditional forms of faith as transmitted by Paul (1 Thess 4:14; 1 Cor 15:3; 2 Cor 5:15; Rom 8:34; Rom 14:15), we notice that there is no mention of the cross. We can therefore think that the first Christians were slow to digest the reality of the cross and to integrate it into their preaching. Why was this? And why did they later find it important to talk about it? Did it really add something to their theological understanding?

- The cross, place of an ambiguous revelation?

In the history of the Church, the integration of the cross into theological reflection has given rise to several twisted visions, such as this theory of penal substitution: while being himself innocent, Jesus would have received the punishment that was due to sinful humanity. God then appears as an irascible judge, infuriated at the sight of sin, who needs to assuage his anger on an innocent man. Such a caricature of the Christian faith has been denounced either by its opponents, such as Michel Bakunin (1814-1876: God and the State, p. 3-5), who echoes the figure of a God always greedy for victims and blood, or by contemporary theologians and exegetes who demonstrate that it is even contrary to Scripture (see Schillebeeckx, Jesus, Parable of God, Paradigm of Man, p. 799 ff).

Nevertheless, several passages of the New Testament contain a certain ambiguity? For example, how can we understand the statement in Col 1:20: "(God was pleased) to reconcile all beings for his sake, both on earth and in heaven, by making peace through the blood of his cross"? By emphasizing the salvific value of the cross, we are affirming that we are sinners in distress and in need of help. How, then, can we understand the role of the cross in our situation as sinners? In particular, we can ask ourselves: is not the death on the cross, that is, a bloody death, responsible for the representation of the death of Jesus as a sacrificial death for sins? We are then faced with the immense challenge of reformulating this representation in terms understandable to our contemporaries.

- The initial shock: "And we were hoping..."

- The plural cross of believers: "I am crucified with Christ" (Gal 2: 19)

- A "Christian idea gone mad"?

Is not giving the word "cross" the symbolic meaning of sorrows, afflictions, trials sent by fate an example of a "Christian idea gone mad", as Chesterton put it? In this case, it would suffice to be a Christian for any form of trial to become a cross, a clear case of abuse of language.

- "He's the reason I'm suffering... " (2 Tim 2: 9)

In the Gospels there are only two passages where the cross is spoken of in relation to the believer: "If anyone wants to follow behind me... let him take up his cross and follow me" (Mk 8:34); "Whoever does not take up his cross and follow behind me is not worthy of me" (Mt 10:38 | Lk 14:27). The cross is seen as a choice, as an option in favour of the service of the Gospel, at the price of renouncing all one's possessions. Thus, the cross is not just any trial, but the result of a specific commitment because of one's faith. Without using the word cross, but rather words like suffering, other passages in the New Testament go in the same direction: "For his sake (Jesus Christ) I suffer to the point of wearing chains like an evildoer" (2 Tim 2:9). There is clearly a commitment "for him" (hyper autou).

- "The stigmata of Jesus I bear in my body" (Gal 6: 17)

While the cross was for Jesus the logical culmination of his fundamental option to serve the Kingdom of God, and for believers it may be the result of their taking a stand in the order of faith, on what condition can painful and unselected experiences of life become crosses? For this is how many believers look at their life of suffering, as for example the eminent theologian Yves Congar, afflicted with multiple sclerosis for more than 20 years, who takes up Col 1:20: "What is lacking in Christ's afflictions, I will complete in my flesh for the sake of his body which is the Church" (see Fr. Yves Congar, "You shall be my people". Interview with André Sève, La Croix-Événement, 5-6 January 1986, p. 10). Is this a good understanding of the New Testament?

What we say about individuals, some say about the Church and even speak of a Church of the Cross, like René Latourelle, referring to persecuted and oppressed Churches (Transcript of Canadian Broadcasting program "Second Regard" (Second look), Fall 1985). Reading the historian Eusebius of Caesarea (3rd century: Ecclesiastical History, VIII, 1, 7) complaining about the softness and nonchalance in the Church with the end of the persecutions, or Emmanuel Mounier, in the 20th century, criticizing routine Christianity for slowly dozing off in its well-being (see Christian Confrontation, p. 12f), one comes to think that the cross should be an intrinsic part of the life of the Church. Again, is this justified in the New Testament?

- A "Christian idea gone mad"?

- Approach

In this exploration of the New Testament witness on the cross, chapters 1 to 4 will focus on the witness of Christ, first the event itself, then its meaning, and chapter 5 on the cross of believers. The aim is to trace the stages of growth of the first Christian communities in their deepening of the mystery of the cross and how they moved from initial scandal to the proclamation of the liberating and unique meaning of the cross.

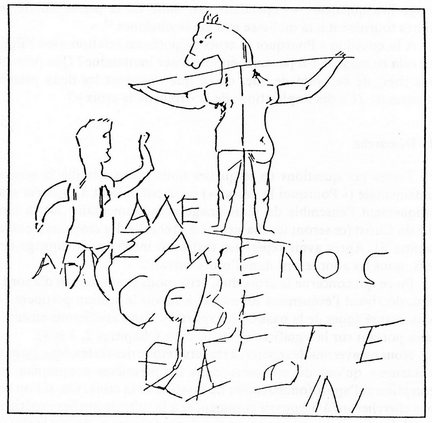

This theological exploration is reflected in the various graphic representations of the cross. On the one hand, the earliest surviving representation is a graffiti known as the "Palatine Crucifix" of pagan origin (Figure 1), which ridicules a Christian in adoration before a crucified donkey head. This is the scandalous and absurd side of the cross.

Figure 1: Crucifix of Palatin Figure 2: Crucifix of Costanza

On the other hand, there is this representation from the 2nd or 3rd century on a piece of carnelian (figure 2), of Christian origin, discovered in Romania (Costanza) and kept in the British Museum, where the crucified Christ is surmounted by the inscription ιχθυς, an acrostic used by the first Christians to express their faith, and surrounded by the twelve apostles: it is now the glorious cross, illuminated by God's intervention and revealing the depth of the mystery of Jesus.

Part one. The event. History and testimony

- The Cross in the Passion Narratives

- "The Son of Man is about to be handed over for crucifixion" (Mt 26:2)

In the Passion narratives, there is no mention of the cross (noun stauros, verb stauroō ) before the scene that describes his condemnation, with the exception of this announcement by Jesus in Mk 26:2.

- Stories in their Present Form - Large Articulations

The synoptic narratives can be divided into three main parts.

Mk Mt Lk 1. Preparations 14: 1-42 26: 1-46 22: 1-46 2. From arrest to conviction "the Son of Man is handed over" 14: 43 – 15: 20 26: 47 – 27: 31 22: 47 – 23: 25 3. From Condemnation to Burial ("The Crucified Son of Man") 15: 21-47 27: 32-66 23: 26-56 - Preparation (Mt 26:2-46)

It is the verb "to hand over" (paradidōmi) that dominates this section of the announcement of the coming passion and recurs 7 times.

- The Son of Man is handed over (Mt 26:47 - 27:31)

The verb "hand over" still dominates this section to describe three steps:

- That of Judas (26: 48; 27, 3-4), representing the disciples

- That of the Jewish leaders (27: 2.18), representing the Jewish religious power

- That of Pilate (27: 26), representing the Roman political power

Now that Jesus has been handed over, all that remains is to move on to the crucifixion stage.

- The Son of Man is crucified (Mt 27:32-61)

This section can be divided into two parts

Description of the event Follow-up or reactions to the event Crucifixion: 27: 32-38 Contempt of passers-by, high priests and bandits: 27: 39-44 Death on the cross: 27: 45-50 Apocalyptic scene, faith of the centurion, presence of women and burial by Joseph of Arimathea: 27: 51-66 Matthew's text has been used, but it only manifests more clearly the major divisions already present in the narrative.

- Preparation (Mt 26:2-46)

- Formation and interrelationships

In fact, when we look at the passion narratives of the four evangelists, especially sections 2 (Jesus handed over) and 3 (Jesus crucified), we note a great kinship. How can we explain this similarity? Here is the most common hypothesis:

- There was originally a primitive account of the passion, a brief account, oral or written;

- This brief account would then have been developed to integrate the narration of everything that led to passion: conspiracy, anointing, betrayal of Judas, denial of Peter, etc.

Things become more complicated when we try to establish the relationship of our Gospel stories before this primitive narrative. For some people, Mark and Matthew, who have a very similar story, would represent two recensions of that same primitive story. For others, Mark alone would have had access to this early account, and Matthew would have taken up Mark's account. Luke's account differs from Mark's in a number of passages and surprisingly contains scenes that are close to John's account, suggesting that there is a common tradition underlying Luke and John. In our analysis, therefore, it will be necessary to make a clear distinction between what is common to the evangelists and what is the specific writing and theology of each.

- Restraint and discretion surrounding the cross

We have already noted that apart from the announcement of Mt 26:2 we must wait for the scene of Jesus' condemnation to find the first mention of the cross. Let us look at those passages where the vocabulary of the cross, the verb stauroō (= V) and the noun stauros (= S) are used.

Mentions Mk Mt Lk 1) 1st Crowd Claim (V) 15: 13 (V) 27: 22 (VV) 23: 21 2) 2nd Crowd Claim (V) 15: 14 (V) 27: 23 3) Pilate's Resolutions (V) 15: 15 (V) 27: 26 (V) 23: 23 4) Jesus led away by the soldiers (V) 15: 20 (V) 27: 31 5) Carrying the cross (S) 15: 21 (S) 27: 32 6) Crucifixion (V) 15: 24 (V) 27: 35 (S) 23: 26 7) Time of Crucifixion (V) 15: 25 (V) 23: 33 8) Company of bandits (V) 15: 27 (V) 27: 38 9) Insults from passers-by (S) 15: 30 (S) 27: 40 10) Insults from chiefs (S) 15: 32a (S) 27: 42 11) Insults from bandits (V) 15: 32b (V) 27: 44 We will have noted the close parallel between Mk and Mt with the same vocabulary, with the exception of point 7). It is quite different with Luke who nevertheless presents us with similar scenes in the same sequence. If we disregard the three "crucify him" of Luke's points 1) and 3), we find ourselves in Luke with only two mentions, points 6) and 7), which describe the scene of Simon of Cyrene helping Jesus carry his cross and the crucifixion of Jesus, two scenes that it would have been impossible to obliterate without keeping us in complete ignorance of how Jesus died.

Thus, in Luke, as in John, there is almost an embargo on references to the cross. How can this be explained? If we accept the hypothesis of a primitive narrative, there are only two possible options: either this restraint on the references to the cross came from the primitive narrative, and it is Mark, later taken up by Matthew, who would have made this development around the cross, or the primitive narrative already contained all these references to the cross and it is the tradition common to Lk-Jn that would have obliterated them.

- Stories in their Present Form - Large Articulations

- The cross and its "environment"

- The crucifixion granted (Mk 15: 1-20 and ||)

The keyword paradidōmi (to hand over) in Mk and Mt allows us to discern two parts:

Mt Mk Lk Jn 1. The Jews hand over Jesus to Pilate 27: 1-14 15: 1-5 23: 1-12 18: 28-38 2. Pilate hands over Jesus to the Jews 27: 15-31 15: 6-20 23: 17-24 18: 39 – 19: 16a In the killing of Jesus, Pilate plays a decisive role, because the Jews do not have this power (see Jn 18:31).

- Jesus handed over by the Jews (Mk 15: 1-5)

- Mark and Matthew (Mt 27: 1-2.11-14)

Both share a very similar story with two questions from Pilate to Jesus, of which only the first is answered ("you say so").

- Luke (23: 1-16)

In Luke's account, we find features that are specific to him:

- Political charges are specified twice (23: 2.5)

- There is no mention of Jesus' silence.

- Pilate clearly states that Jesus is innocent, a view also supported by Herod, whom only Luke mentions.

An analysis of the vocabulary in this story shows that it was written by Luke. And his intention is clear when we read the reference to this account in the Acts of the Apostles (4:27): Jesus is truly innocent, but nevertheless the word of God in Psalm 2:2 came true when it announces that "kings" and "rulers" have gathered against the Messiah in Jerusalem.

- John (18: 29-38)

It is the most elaborate of the stories, both in regard to Pilate's dialogue with the Jews (18:29-32) and his dialogue with Jesus. Like Luke, John emphasizes the innocence of Jesus.

- Mark and Matthew (Mt 27: 1-2.11-14)

- Jesus handed over by Pilate (Mk 15: 6-20)

All the evangelists tell of Pilate's effort to free Jesus and the rejection of the crowd who prefer Barabbas. Within this basic setting, the stories vary.

- Mark (15: 6-20) and Matthew (27: 15-31)

After having objectively reported the arguments of the accusation, the two evangelists make a value judgment: Pilate acknowledges that it was out of jealousy that Jesus was handed over, and it is not so much the crowd as the chief priests, stirring up this crowd, who are responsible for the condemnation of Jesus. Matthew reinforces this judgment with the intervention of Pilate's wife pointing out Jesus as righteous and with Pilate himself washing his hands to distance himself from this condemnation.

- Luke (23: 17-24)

In Luke's, this section is shorter. But his ideas are clear: three times Pilate insists that he finds nothing wrong with Jesus, and the section ends with Pilate handing Jesus over, not to be crucified, but to be handed over to the will of the Jewish religious leaders. The Acts of the Apostles will again return to the idea that they are responsible for his death (2:36; 3:13; 4:10; 13:28).

- John (18: 39 - 19: 16a)

Like the other evangelists, John takes up the idea that Pilate considers Jesus to be innocent and, if he has him scourged, it is only a ploy to try to save him. Of course, all this is told in his particular style where he develops Pilate's dialogues with the Jews and with Jesus, and where the figure of Jesus appears in perfect mastery of the situation.

In short, the four evangelists insist on the non-culpability of Jesus and the injustice of his condemnation. This is particularly emphasized in Luke, who mentions the cross as little as possible and places all the responsibility for it on his Jewish opponents. By insisting so much that this punishment was not imposed by the Roman authorities, does this not betray a great embarrassment in the face of the crucifixion, the punishment that was imposed for serious crimes?

- Mark (15: 6-20) and Matthew (27: 15-31)

- Jesus handed over by the Jews (Mk 15: 1-5)

- Crucifixion accomplished (Mk 15:21 ||)

Again, the stories of Mark and Matthew are very close. Using them as a point of comparison, we can see in Luke and John the absence of certain elements, such as the wine that is given to Jesus or his cry. On the other hand, we find in them more developed points such as the bearing of the cross or the inscription on the cross, or a modified order of the elements. But what is special about all these stories is the abundance of references to Scripture. This is a sign that all the elements surrounding the crucifixion have been deepened either by the pre-evangelical tradition or by the evangelists themselves.

- Scriptural reference

- Types of references

- The explicit quotation introduced by a formula of fulfilment and which we find only three times and only in John: "For this has happened so that the Scriptures might be fulfilled..." (cf. Jn 19:36)

- a sometimes textual quotation from the Old Testament, but without explicitly mentioning it, such as the reference to Psalm 22:2 in Jesus' cry in Mk 15:34: "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?"

- a simple allusion, sometimes very subtle, to a passage of Scripture that we recognize only by affinities of context and vocabulary, such as this allusion to Psalm 22:19 when they share Jesus' garments in Mk 15:24. This type of reference is the most frequent in the passion narratives.

- Evidence of ancient use

It was probably very early on that Christian communities got into the habit of rereading Scripture to try to understand the events surrounding the death of Jesus. A clue is provided by the fact that a reference such as Psalm 22:19 ("they divide my garments among themselves and cast lots for my garment") is found in all four stories, which can only be explained by the existence of a primitive narrative or a very ancient tradition.

- Tendency to introduce a reference where it was not present.

One can imagine that the events surrounding the death of Jesus were initially told for themselves, but as Scripture was reread to find echoes of these events, they took on a theological dimension over time. This can be seen, for example, in the accounts of Matthew and Luke, written around 80 or 85, and therefore much later than Mark's. The events surrounding the death of Jesus were first told for themselves, but as we reread Scripture to find echoes of these events, they took on a theological dimension over time:

- While Mk 15:23 simply writes: "They were giving him wine, having been mixed with myrrh", Matthew changes the tense of the verb "to give" and replaces "myrrh" by "gall" ("They gave him to drink wine mingled with gall") to evoke Psalm 69:21.

- Luke 23:30 speaks of Hosea 10:8 in a passage of his own: "Then they will begin to say to the mountains, 'Fall upon us', and to the hills, 'Cover us'".

- Tendency to develop and make a reference clearer

In the same setting where Matthew reuses Mark's account, we can identify three passages where Matthew corrects Mark when he refers to Scripture by sticking closer to the text :

- Mt 27:35b opts for the verb in the past tense (they divided my garments among them) as in the Greek text of Psalm 22:19 rather than the verb in the present tense in Mark 15:24b.

- Matthew 27:45 opts for the adjective "all" as in the Greek text of Exodus 10:22 (darkness was over all the land) rather than using the expression of Mark 15:33: over the whole land.

- Mt 27:50-51 establishes a clearer link with the Greek text of Psalm 18 by modifying the expression "having uttered a loud voice" in Mark 15:37 to introduce the verb to shout (having cried again in a loud voice) used in the psalm, and by adding the mention that the earth is stirring and shaking as in the psalm.

- Tendency to make explicit an implicit reference

A typical example is John 19:24b, who clearly writes that he is referring to Scripture (a passage on Jesus' tunic that is not torn): "that the Scripture might be fulfilled".

- Scriptures as witness

Even if the psalms are given place of choice, in particular Ps 22 and Ps 69, in the accounts of the passion, it is to the whole of Scripture, presented by Luke 24:44 under the title of the Law of Moses, the Prophets and the Psalms, that reference is made to speak of the different aspects of the mystery of Jesus.

- Types of references

- "Narrative theology"

We know that the passion narratives are not just about reporting events. For the evangelists seek above all to transmit the meaning of events, to do catechetical work. They do this in two ways: first, by introducing references to Scripture, as we have seen, but also by making a selection from the scenes to be told and their sequence. This last facet is clearly seen in John when he places the spotlights on the inscription of the cross, the presence of Mary, the piercing of Jesus' side. Let us give examples from the synoptics.

- Mark 15: 38

How can we interpret the scene where the curtain of the Temple is torn in two, from top to bottom, when Jesus dies? The whole context gives us the key to interpretation. For the scene that follows is that of a centurion, a non-Jew, proclaiming his faith. In the scenes that preceded, there were charges from the Sanhedrin against Jesus wanting to destroy the Temple, charges that were repeated in the form of mockery on the cross. Mark's intention becomes clear: the old Temple with its curtain, which restricted access to God to Jews only, is indeed destroyed or torn down, because this access is now open to all, including the Gentiles.

- Matthew 27: 51-53

This scene tells the story of the earth trembling after Jesus' death, the rocks splitting and the dead rising. In the Old Testament and intertestamentary literature, such imagery is associated with the great "Day of Yahweh", with his final and definitive intervention for the salvation of his people. Thus, the eschatological and salvation times of God have truly begun, and to underline this, Matthew associates the centurion's proclamation of faith not with the sight of Jesus' death as in Mark, but with that of cosmic phenomena.

- Luke 23: 27-31

This scene tells the story of Jesus' meeting with women from Jerusalem who are beating their breasts and lamenting, and whom Jesus invites instead to lament over their children, dry wood compared to green wood like him. Why does Luke put the spotlight on such a scene, if not to insist once again on Jesus' innocence?

- Mark 15: 38

- Scriptural reference

- The crucifixion granted (Mk 15: 1-20 and ||)

- The reflection of a long journey

- The effort to interpret the events surrounding the death of Jesus, as we have seen, does not focus on a single particular fact, but on a set of details, sometimes banal or routine, that surround this event, what we might call the environment of Jesus' death. As we have also seen, this effort was spread out over time, and only gradually was it possible to deepen the meaning of the events.

- But what is surprising is that, in spite of everything, the mention of the crucifixion remains extremely terse: "It was the third hour when they crucified him" (Mk 15:25); "they crucified him and two others with him: one on either side and Jesus in the middle" (Jn 19:18). And there is not even a reference to Scripture to try to shed light on this crucifixion. When we look at the old Creed, like the one reported by Paul ("Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures", 1 Cor 15:3), there is not even a reference to the crucifixion. Why not? Doesn't all this indicate discomfort and embarrassment about the crucifixion itself?

- We have already pointed out that an evangelist like Luke makes an effort to mention the cross as little as possible and constantly insists on demonstrating Jesus' innocence. All this only confirms that the cross was a problem, and that it took a long time to deepen the whole mystery, as echoed in the scene of the disciples of Emmaus where Jesus reproaches them for being unintelligent and slow to believe (Lk 24:25-27).

- "The Son of Man is about to be handed over for crucifixion" (Mt 26:2)

- "Crucified under Pontius Pilate" - "This despicable mystery, full of shame"

What was the practice of crucifixion in the first century and how was it perceived? We have an echo of this in Paul who speaks about the year 55 "a scandal to the Jews and folly to the Gentiles" (1 Cor 1:23).

- "Madness for the heathens"

The Greek term for the cross of Jesus throughout the New Testament is stauros, which refers to any form of upright or erected stake or post. As an instrument of torment, it refers to the pole used for executions by hanging, impalement or strangulation. When the evangelists report that Jesus had to carry his cross, the Latin patibulum is referred to as the horizontal beam that was fixed either above (T) or in the middle (+) of a vertical post (the stauros) in the strict sense, which remained permanently planted.

- Crucifixion as Capital Punishment

This practice seems to date back to the Persians as Herodotus and Thucydides (5th century) testify. Among the Greeks, we have an echo of it in the 4th century at the time of Alexander the Great and Plato. This practice seems to have passed to the Romans in the 1st century BC through North Africa, especially Carthage, and in the first century AD it was well known in the different regions of the empire.

- Servile supplicium (torment for slaves)

This method of execution was reserved only for criminal slaves, as Cicero (1st BC) clearly states, and could never be applied to Roman citizens. Thus, "torture of slaves" was synonymous with crucifixion, as we see in Tacitus (1st century AD). And there was no doubt about its cruelty, as Plato notes and as described by Seneca (1st century AD).

- Crucifixion as Capital Punishment

- "Scandal for the Jews"

- A known practice

Crucifixion was also known in Palestine. It is the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus who tells of various crucifixions, mostly carried out by foreign rulers, from the 2nd century BC to the present day.He notes a number of mass crucifixions, such as the one against the 800 Jews, Pharisaic opponents, ordered by the Hasmonean Jew Alexander Jannaeus (88 BC), or against the 2,000 men during the uprising of Judas in the time of Archelaus (4 BC - 6 AD). Most of the time the victims are people who are considered rebels, bandits, terrorists or agitators.

Apart from Josephus, there are few attestations: a text from cave 4 of Qumran which seems to allude to the crucifixion of a Pharisee under Alexander Jannaeus, an allusion in the Assumption of Moses, a Jewish apocryphal, to the mass crucifixion during the revolt of Judas the Galilean. On the archaeological level, there is the ossuary of a man who apparently died crucified, discovered in 1968 in Giv'at ha-Mivtar and dating from the 1st century AD.

- ... and reproved: "Cursed be he who hangs on the tree"

The Jew Flavius Josephus uses several adjectives to describe the crucifixion: the most pitiful of the dead, of unheard-of cruelty, repulsive. But for a Jew of the 1st century, the most terrible judgment is theological: Crucifixion is a curse of God according to Deuteronomy 21:22-23 ("If a man guilty of a capital crime has been put to death and you hang him on a tree, his body may not be left on the tree by night; you shall bury him the same day, for a hanging man is a curse of God, and you shall not defile the ground which the Lord your God gives you for an inheritance".). The expression "hanging from a tree" was understood as referring to crucifixion in Judaism contemporary with Jesus, as is implied in the text from Qumran cave 4, which speaks of "men hanging alive on the tree" in reference to the mass crucifixions of Alexander Jannaeus.

- A known practice

- Handicap for Christians

Knowing the feelings of horror at the mention of a crucified man, it is easy to imagine the reaction of an audience when they were told about a Jesus, the Messiah and Son of God: there was nothing more implausible and preposterous.

- The silence

Apart from the immense disappointment we see in the disciples of Emmaus, a first attitude that we observe among the first Christians is to remain silent on the cross, and to simply say that Jesus died, without mentioning the method of execution. This is what we see in the pre-Pauline forms, those hymns and confessions of faith that are placed in the twenty years following the death of Jesus and in which the verb stauroō (to crucify) and the noun stauros (cross) are totally absent. Here are some of them:

- we believe that Jesus died and rose again (1 Thess 4: 14)

- Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures..., that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures, (1 Cor 15: 3s)

- ...It is Christ Jesus, who died, yes, who was raised, who is at the right hand of God... (Rom 8: 34)

- He was put to death in the flesh, but made alive in the spirit. (1 Pet 3: 18)

- Defensive

The second attitude is to sometimes mention the cross, but immediately coupled with the proclamation of the resurrection by God. Or else the verb "to hang" rather than to crucify is used, alluding to Deut 21:22 in order to place all the responsibility for this action on the Jewish people and insisting on God's intervention in favor of Jesus. This is what we observe in the discourses of Peter and Paul in the Acts of the Apostles where an echo of the primitive kerygma slips in. In this way one avoids focusing all attention on the cross, placing the emphasis instead on the divine action that repairs the evil of human action.

- The silence

- "Madness for the heathens"

Part two. From Failure to Fecundity - Progressive Development of a Theology of the Cross

It took a long journey for the first Christian communities to see the cross differently and to read in it not only a revelation about Christ, but also a revelation about God and about ourselves. Let us examine this journey.

- The cross as an unveiling about Jesus Christ and God

- Manifestation of obedience (Phil 2:8)

Here we have probably the oldest known example of the Jewish-Christian hymn prayer of early Judaism, dating from before Paul's writings.

- The hymn and its structure

The whole hymn has two parts, the humbling of Christ (verses 6-8) and the exaltation of Christ (verses 9-11). Let's look at the first part, which deals with the cross.

I II 6a him being (participle) in [the] FORM

of God7c HAVING BECOME (participle) in [the] likeness of men 6b did not considered as something to grasp to be equal with god 7d and having been found in appearance

as a man7a but he emptied himself 8a he humbled himself 7b having taken (participle) [the] FORM of a slave 8b HAVING BECOME (participle) obedient unto death 8c and [the] death of [the] cross By dividing verses 6-8 into two stanzas, we end up with a text of great symmetry: stanza I begins with a participle and the word "form", and also ends with a participle and the word "form", while stanza II begins with the participle "having become" and also ends with the participle "having become". There is also symmetry between stanzas I and II: to the words "God" in I correspond the words "God" in II. The stanza affirms that Christ left his condition of God to become a slave, stanza II makes explicit what this means: to take the human condition to the point of assuming death itself, in a gesture of pure fidelity.

- Thanatou de staurou (death of the cross), Pauline addition

Let's look at correspondences in structure, ideas and vocabulary:

6a in form of God 7c in the likeness of men 6b equal with God 7d as a man 7a he emptied himself 8a he humbled himself 7b having taken... slave 8b having become obedient unto death The symmetry is total without the mention of the cross, which then appears as an addition by Paul. In fact, the cross is absent from the pre-Pauline hymns, and such an addition on the part of Paul corresponds completely to his theology (see Phil 2 and 3).

- A reference to Ebed Yahweh (servant of God)?

The answer to that question is no. Even though the first Christians made much use of the poems of the suffering servant ( Isa 42:1-9; 49:1-6; 50:4-9; 52:13-53:12) to understand the sufferings endured by Jesus, there is no trace of them here. Above all, there is no mention of Christ's sufferings and their redemptive value.

- The supreme expression of a double relationship

Regardless of whether the addition of the reference to the cross is by Paul or another author, one can question the meaning of the cross in this context. In fact, the cross expresses a double relationship. First, it is the expression of a relationship with God maintained to the extreme point of its demands; it has no value in itself, but it is the result of faithfulness to the end. But the cross is also a communion with the human condition and destiny, to the point of embracing the extreme of human misery.

-

"So God highly exalted him..."

The cross would be meaningless without what follows, the glory that awaits the one whom God has exalted. Let us remember that it is not only death on the cross that leads to resurrection, but the faithful and available existence of which it is the supreme expression.

- The hymn and its structure

- Manifestation of "weakness" (2 Cor 13:4)

For he was crucified in weakness, but lives by the power of God. For we are weak in him, but in dealing with you we will live with him by the power of God.

In other words, Christ was weak to the point of being crucified.

- A double antithesis

We find the same antithesis as in Phil 2:

Phil 2 he humbled himself... ...therefore God unto the cross highly exalted him

2 Cor 13 in weakness by the power of God he was crucified he lives To the attitude of lowliness and weakness responds the powerful intervention of God. Therefore, Paul intends to model his pastoral attitude to the Corinthians on that of this weak Christ, so that God may unfold his power.

- The poverty of the "collaborator of God"

What does Paul mean by the word "weakness" (astheneia)? In the previous two chapters he uses it five times in reference to his own experience as an apostle. It refers to the attitude of humility and lack of pretension in his pastoral action, where he refuses to assert himself with power and to intervene vigorously to impose himself. We are very close to the thought of Phil 2, except that it is no longer a question of the condition of pre-existence which Christ renounced, but of a certain type of existence and human behavior which Paul renounced.

- A double antithesis

- Manifestation of constancy (Heb 12:2)

The cross in Hebrews 12:2 still fits into the pattern of humbling and exaltation:

humbling ...Jesus who instead of the joy that was set before him endured the cross, disregarding its shame

exaltation and has taken his seat at the right hand of the throne of God This verse cannot be isolated from its context, which exhorts believers to constancy, concord and humility, and must be analyzed.

- Christ Archēgos, model in ordeal

We use sports imagery where the believer is called to run an event, and therefore must show his endurance, his constancy, his perseverance. To help him, he has the example of Christ, called archēgos, i.e. leader or model, who has been able to resist sin. Within this setting, the cross receives two different perspectives.

- The cross is first presented as a manifestation of endurance.

The believers (v. 1) Christ (v. 2) with endurance (di’hypomonēs) instead of the joy lying before him (prokeimenēs) let us run the contest he endured (hypemeinen) lying before us (prokeimenon)... a cross... Christians are invited to endure the trial as Christ endured the cross. But in the latter case, to endure the cross implied a choice, i.e., to renounce the joy placed before him, more precisely, to renounce the temporary escape from death as presented in Gethsemane (see Hebrews 5:7). The cross appears as the expression of an option of fidelity maintained to the end, to the point of accepting an untimely death.

- The cross is also presented in relation to sin

For the latter represents the trial that assails the Christian. Now, for Christ, sin was above all the opposition he encountered and which led to his death. But for the Christian, it signifies his participation in this first opposition, thus making Christ again undergo the trial of the cross. Yet, through the cross, Christ struggled to the point of giving his life against sin, which the Christian cannot do.

- The cross is first presented as a manifestation of endurance.

- Cross of Christ and Christian motivation

Our analysis of Hebrews 12:1-4 has shown that the cross must be a source of inspiration for the Christian: Christ expressed his faithfulness to the point of blood and thus led to exaltation; Christians in turn must show endurance in the face of the experience of sin, knowing that it leads to the communion of God, following him who sat at the right hand of the throne of God.

- Christ Archēgos, model in ordeal

- The cross as an unveiling about God - The testimony of 1 Cor 1-2

It is with the first epistle to the Corinthians that Paul uses for the first time the terms stauroō (crucify) and stauros (cross), especially in the first two chapters where they appear six times, that is a third of all Pauline uses.

- "God's weakness is stronger than men" - The testimony of 1 Cor 1-2

Chapters 1-4 form a whole, the structure of which can be established as follows:

- Part One (1: 10 - 2: 16)

- Community situation and first reaction (1: 10-17)

- Wisdom of God and wisdom of the world (1: 18 - 2: 16)

- opposites in relation to the preaching of the Gospel (1: 18 - 2: 5)

- object (1: 18-25)

- addressees (1: 26-31)

- the method of transmission (2: 1-5)

- opposites as to acquisition method (2: 6-16)

- opposites in relation to the preaching of the Gospel (1: 18 - 2: 5)

- Part Two (ch. 3-4)

- Back to the community situation (3: 1-4)

- The preachers in the community (3: 5 - 4: 21)

- The role of preachers in relation to the community (3: 5-17)

- The community's attitude towards preachers (3: 18 - 4: 21)

- Part One (1: 10 - 2: 16)

- The situation of the community

Paul responds by affirming that Christian preaching focuses on the event of the cross. The idea of a crucified Messiah appears to the world as madness and scandal, and contradicts common sense and human reason. Above all, it contradicts the image we have of a God who manifests his salvation by works of power, and reveals instead his "folly" and "weakness". All this must be reflected in preaching with its message centred on scandal and folly. For this is how God wanted to offer His salvation, manifesting His power and wisdom in this way. The Corinthians must not forget that the Gospel is not a theoretical assembly of ideas satisfying the mind, but an event, and an event totally confusing to the mind.

- The Gospel and its object: "We preach a crucified Christ"

Paul responds by affirming that Christian preaching focuses on the event of the cross. The idea of a crucified Messiah appears to the world as madness and scandal, and contradicts common sense and human reason. Above all, it contradicts the image we have of a God who manifests his salvation by works of power, and reveals instead his "folly" and "weakness". All this must be reflected in preaching with its message centred on scandal and folly. For this is how God wanted to offer His salvation, manifesting His power and wisdom in this way. The Corinthians must not forget that the Gospel is not a theoretical assembly of ideas satisfying the mind, but an event, and an event totally confusing to the mind.

- A transmission mode adapted to the object: "...weak, fearful and all trembling"

If the power of God was manifested through the event of the cross, it is also manifested in the poverty of the means to make it known, contrary to what the wisdom of the world values. To be convinced of this, the Corinthians need only look at themselves: a community that is insignificant by the standards of the world, without sages and people of high birth. They therefore make a mistake in evaluating preachers by the rhetoric and wisdom of this world, when God is able to act through the poverty of a proclamation that lacks the prestige of word and wisdom, as was the case with Paul himself.

- "...they would not have crucified the Lord of glory" (1 Cor 2: 8)

Finally, the cross represents human misunderstanding of God's wisdom. Indeed, human wisdom, represented by the various levels of authority, especially religious authorities, has been unable to understand God's wisdom and has crucified the very one whom God has glorified. The antithesis is total.

- "God's weakness is stronger than men" - The testimony of 1 Cor 1-2

- Manifestation of obedience (Phil 2:8)

- The cross as an unveiling about ourselves

- The double meaning of the cross - 1 Pet 2, 22-25

This text is set in a context in which Peter exhorts the servants to be persevering, taking the suffering Christ as a model.

- Him / You

Verses 22-24 can be broken down as follows:

This is the model for the believer. As for verse 25, it marks a break and does not really respond to vv. 20-21.

- Revival or echo of a tradition?

Despite the fact that this well-structured set might suggest a traditional form, it is probably a composition by the author of 1 Pet, but which perhaps echoes ancient tradition in three ways.

- The expression "Christ suffered for you" (v. 21b) seems to echo early tradition and was common in pre-Pauline creeds or hymns.

- It is typical of the early tradition to use xylon (wood) instead of stauros (cross), thus referring to Deut 21:23.

- Vs. 22, 24 and 25 all refer to Isa 52 - 53, the fourth song of the Servant.

- Christological reading of Isa 52:13 - 53:12

1 Peter 2: 22-25 Isa 52: 13 - 53: 12 (LXX) 22 he who did not do sin 53: 9 he did not do iniquity neither was found neither was found deceit deceit in his mouth in his mouth 23 who being reviled was not reviling in return; suffering, he was not threatening 53: 7... And he, because of his affliction, opens not his mouth But handing [himself] over to Him judging righteously 53: 6 the Lord handed him over for our sins 24 who bore himself our sins 53: 4 He bears our sins 53: 11 and he shall bear himself their sins 53: 12 and he bore the sins of many... in his body on the tree so that having been dead to the sins, we might live to riighteaousness 53: 11 (heb.) the righteous one, my servant, shall make righteous many by whose wounds you have been healed 53: 5 by his wounds we were healed 25 For, you were like sheep going astray but you have returned now to the shepherd and the overseer of your souls 53: 6 All like sheep we have gone astray The borrowings of this letter of Peter from the text of Isaiah are very clear. And this is not a unique case, since the same thing is noted in Rom 4:23 and Acts 3:13; this probably indicates a traditional usage. But what must be emphasized is that this passage from Isaiah is the only one in the whole Bible where the death of one man is related to the sins of others. We are thus faced with a new development in the theology of the cross.

- Exemplarity and salvation

- The author first presents Christ as the model of believers who have to suffer unjustly: if you have to suffer, he says, then suffer like him by renouncing to return evil for evil.

- But he goes further, saying that Christ took our sins upon himself in his body on the tree so that, dead to sin, we might live for righteousness. How can we understand this statement?

- In addition to using the text of Isaiah, the author refers here to Deuteronomy 21:22-23 (When someone is convicted of a crime punishable by death and is executed, and you hang him on a tree,...). For the cross was a punishment reserved for sinners, and therefore Christ knew the fate of sinners.

- But referring to the text of Isaiah, the author makes it clear that Christ was without sin (v. 22).

- It was therefore our sins that he took upon himself by freely accepting the cross: his fidelity and obedience redeemed our infidelities and disobedience.

Thus, in taking upon himself our sins, it is not said that Christ would have suffered in our place, but that by accepting an unjust suffering coming from men, he has turned the situation in our favour: his death becomes a death for us.

- Him / You

- "Christ crucified has been clearly presented to you" - The letter to the Galatians

The context of Paul's letter to the Galatians is that of a crisis provoked by " Judaizers ", i.e. Christians of Jewish origin who advocated the return of circumcision and a certain number of Jewish practices, as required by the Law. Paul answers them: By doing this, you cancel the scandal of the cross. Let us take a closer look.

- Cross of Christ and curse of the law

Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us for it is written, "Cursed is everyone who hangs on a tree" (Deut 21: 23) in order that in Christ Jesus the blessing of Abraham might come to the Gentiles, so that we might receive the promise of the Spirit through faith. (Galatinas 3: 13-14)

Paul's argument revolves around two points: Abraham and the curse of the Law.

- Abraham was promised to be the father of a multitude four hundred and thirty years before the existence of the Law (Gal 3:17). He was the first to be justified because of his faith (Gal 3:6). Thus, those who claim faith are the true sons of Abraham.

- The curse first refers to death on the cross as Deut 21:23: Christ therefore took upon himself this curse from the Law. But the curse also refers to Deut 27:26 (Cursed be anyone who does not uphold the words of this law by observing them) where the curse is called upon all those who do not observe the Law completely, which implies everyone, because no one can boast of observing the Law completely. Therefore, the Law cannot save anyone. That is why, by accepting to be cursed by the Law through his death on the cross, Christ renders the Law null and void and thus frees us from it, and thereby takes us back to the time of Abraham, where we are justified by faith, which opens the door to non-Jews.

Paul's exegesis may seem very rabbinic, but it has the consequence of bringing to the forefront a contentious point, and of transforming an event on which one had remained very discreet to put it at the centre of Christian preaching.

- "I am crucified with Christ" (Gal. 2:19)

To fully understand this verse, we must compare it to a similar passage in the Epistle to the Romans.

Gal 2: 19 Rom 6 ... I died through the law 2 we who died to sin 10a he (Christ) died to sin once for all... 11a so you also must consider yourselves dead to sin to that I might live to God; 10b ... and he lives to God 11b ... (consider yourselves) alive to God in Christ Jesus I have been crucified with Christ our old self was crucified with him In both texts we have the same antithesis (die to / live to) and the same expression: crucified with. Fundamentally, Paul affirms this: Since the Law is powerless to give justification, it forces me to leave it, to die to it, and thus to die to all the sins it pointed out to me, in order to cling to Christ and live for God; thus clinging to the Christ of the cross, I am crucified with him, because I take advantage of its liberating effect with respect to sin.

- Death of Christ and the Cross of Christ

Paul therefore affirms that the death of Christ freed mankind from its sins. But how can we understand the exact meaning of this statement? Two texts will help us in particular.

- Romans 8: 3

For God has done what the law, weakened by the flesh, could not do: by sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh, and to deal with sin, he condemned sin in the flesh.

The expression "because of sin" is the one used in the Bible in the ritual of sacrifices for sin (see Leviticus 4-6). In trying to understand the meaning of Jesus' death, early Christians are led to refer to the sacrificial regime of the temple, which included animal sacrifices and was related to the forgiveness of sins. This was all the more understandable since the death of Jesus, like the sacrifices for sin, had involved the shedding of blood. For a Christian of Jewish origin and familiar with the sacrificial rite, this way of understanding the death of Jesus was quite natural.

- Romans 3: 25

whom God put forward as a sacrifice of atonement by his blood, effective through faith.

The mercy seat is the lid that closed the Ark of the Covenant in the holy of holies in the Temple of Jerusalem. Paul refers to the ritual of Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) where the high priest once a year sprinkled the mercy seat with blood to signify the purification of sin (see Lev 16). Again, for a Jew, the association of the bloody death of Jesus with this ritual is quite natural.

In short, if Paul was the first to put the cross at the centre of his preaching, he was able to benefit from the reflection of the entire Christian community which, very early on, began to understand the death of Jesus in the sacrificial line.

- Romans 8: 3

- Cross of Christ and curse of the law

- "...making peace through the blood of his cross" - The Letters from Captivity

With letters of captivity such as those to the Colossians and Ephesians, there is a change of emphasis: instead of expressing Christ's death in a negative way as an atonement for sins, it is expressed in a positive way as provoking rapprochement and reconciliation.

- Affinities and differences

...by making peace through the blood of his cross. Col 1, 20

This verse is inserted in a Christological hymn of sapiential source and formed of verses 15-20.

A 15a he who is image of the invisible God,B 15b firstborn over all creation, A118b he who is the beginning,C 16a for in him all things were created... D 16b all things have been created through him and unto him 17a and he is before all things...

E

18a and he is the head of the Body, the Church,B118c firstborn out from the dead We will have noted the parallelism of the structure where the same expressions are echoed (underlined by the same colours). The first part celebrates the primacy of Christ in the order of creation, while the second (vv. 18-20) deals with the primacy of Christ in the order of salvation. If Paul is inserting here a hymn that already existed, he probably added v. 20b (having made peace by the blood of his cross), which we have somewhat isolated from the whole hymn; for the same vocabulary and themes are found elsewhere in the letters of captivity. To understand how the cross is a source of reconciliation, we must turn to the letter to the Ephesians for more precision.C119 for in him was pleased to dwell all the fullness D120a and through him to reconcile all things to himself 20b having made peace by the blood of his cross...

- The cross and the reconciliation of humanity

13 But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near by the blood of Christ. 14 For he is our peace; in his flesh he has made both groups into one and has broken down the dividing wall, that is, the hostility between us. 15 He has abolished the law with its commandments and ordinances, that he might create in himself one new humanity in place of the two, thus making peace, 16 and might reconcile both groups to God in one body through the cross, thus putting to death that hostility through it. -Ephesians 2: 13-16

Like the Law, this barrier which separated Jews and Gentiles, circumcised and uncircumcised, has been abolished by the cross of Christ, no longer being a source of justification, there follows a great reconciliation of all humanity, forming one people and justified solely by faith in Christ.

- The cross and reconciliation with God/a>

And you who were once estranged and hostile in mind, doing evil deeds, he (God) has now reconciled in his fleshly body through death, so as to present you holy and blameless and irreproachable before him -Colossians 1: 21-22

The reconciliation brought about by Christ's death on the cross does not only concern humanity, but also God: with death to sin the enmity with God has disappeared. Several passages in the letters of captivity mention this remission of sins and new life in Christ (see Col 1:14; 2:13; Eph 1:7; 2:1.5). How can we understand this reconciliation with God through the cross? Perhaps we must once again imagine that the analogy with the sacrifices for sins in the temple led the first Christians to interpret Christ's bloody death in this way.

- The cross and the abolition of the debt

13 And when you were dead in trespasses and the uncircumcision of your flesh, God made you alive together with him, when he forgave us all our trespasses, 14 erasing the record that stood against us with its legal demands. He set this aside, nailing it to the cross. -Colossians 2: 13-14

The essential idea is expressed in v. 13: through Christ we have been freed from sin and from our faults that accused and condemned us before God. All this is known to us. But what is new is the expression in v. 14 "the record that stood against us". What does this mean? The image refers to an IOU. The sins of mankind made her an insolvent debtor to God. But thanks to the cross of Christ, that debt has been erased.

- Moral Implications - From Gift to Requirement

For Paul, justification by the cross of Christ is offered free of charge: it is a gift. On the other hand, this gift has consequences: we are called to live according to this new life. It is the use of the analogical meaning of the word "crucify", i.e., to kill, to make disappear, to break with, that will enable him to translate his thought.

And those who belong to Christ Jesus have crucified the flesh with its passions and desires. -Galatians 5: 24

For Paul, there are two opposing regimes: that of the flesh and that of the Spirit. The Christian is freed in principle once and for all from the regime of the flesh, but every day he must crucify (i.e. make an effort to break with) the elements of this regime.

We know that our old self was crucified with him so that the body of sin might be destroyed, and we might no longer be enslaved to sin. . -Romans 6: 6

Liberation is a fait accompli (our old man was crucified) and we are no longer slaves to sin, yet later on Paul exhorts the believer to change from day to day (Rom 6:12): the good news has requirements.

May I never boast of anything except the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, by which the world has been crucified to me, and I to the world. . -Galatians 6: 14

Paul calls upon the Judaists who seek glory in a return to circumcision. In alluding to his crucifixion in relation to the world (the world is crucified for me and I for the world), he intends to recall that he himself renounced all the privileges that being circumcised gave him, Hebrew of the tribe of Benjamin, Pharisee and Apostle, in short, what the world considers important and prestigious, breaking with a purely human search for interests and influence.

- The cross and the abolition of the debt

- Affinities and differences

- The double meaning of the cross - 1 Pet 2, 22-25

Part three. From the cross of Christ to the cross of Christians

- The cross arising from the reception and service of the Gospel

- Ordeal and service

We can find in St. Paul a certain "mysticism" or "spirituality" of the cross. Let's take a closer look.

- "Persecuted for the cross of Christ" (Gal 6:12.17)

- Galatians 6: 12 : It is those who want to make a good showing in the flesh that try to compel you to be circumcised - only that they may not be persecuted for the cross of Christ.

- Galatians 6: 17 : From now on, let no one make trouble for me; for I carry the marks of Jesus branded on my body.

The context is that of the Judaizers, those Christians who advocate a return to circumcision, because they seek prestige, according to Paul, and because they wish to avoid the trouble that opposition to the Jewish Law would entail. The persecutions mentioned here are probably to be understood in the sense of real physical abuse, i.e., the mistreatment that results from the preaching of the cross of Christ. It is in this sense that Paul's expression "I bear in my body the marks of Jesus" is to be understood. On several occasions Paul refers to what the preacher of the Gospel must suffer: to be hungry, thirsty, mistreated, insulted, slandered (see 1 Cor 4:10-12; 2 Cor 4:8-10).

- "...what is lacking in the afflictions of Christ."

- Colossians 1: 24 I am now rejoicing in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I am completing what is lacking in Christ's afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church.

Let us make it clear right away that Paul is not saying that the redemptive value or significance of Christ's passion and death is lacking. But the idea is this: in order to be known, salvation must be proclaimed by preachers who accept to face persecution and suffering, following the example of Christ; and it is through this difficult proclamation of the Gospel that the Body of Christ, the Church, grows. What is to be completed, then, is the preaching and growth of the Body of Christ (see 2 Timothy 1:8-12; 2:8-10).

- "Persecuted for the cross of Christ" (Gal 6:12.17)

- "Whoever wants to follow me takes up his cross" (Mk 8: 34 ||)

The context of this text is that of Peter's confession of faith at Caesarea Philippi, followed by the first proclamation of his passion by Jesus against which Peter protests. It is at this point that he invites his audience to take up the cross.

(In the parallel texts that follow, words similar to the three evangelists are underlined, those that are unique to them are in italics, and those shared by Matthew with Mark are in blue.)

Mark 8 Matthew 16 Luke 9 34 He called the crowd with his disciples, and said to them, " If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. 24 Then Jesus told his disciples, " If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. Then he said to them all, " If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross daily and follow me. 35 For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the Gospel, will save it. 25 For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it. 24 For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will save it. - One requirement among others?

The demand to take up the cross is framed by the demand to deny oneself and the demand to accept to lose one's life. Since "taking up one's cross" and "losing one's life" are found elsewhere in the Gospels (Mt 10:38; Lk 14:27; 17:33), it can be thought that these statements circulated in isolation and independently and the evangelist inserted them here and there to support the themes he was dealing with.

- Different perspectives/a>

The three evangelists have very similar versions of Jesus' call, as the underlined words show, but there are differences, especially in the audience Jesus addresses.

- Matthew: the Twelve

In Matthew, behind the disciples we must see the Twelve, as is usually the case, and as confirmed here by the fact that he addresses those who are with him at Caesarea Philippi and for whom Peter is the spokesman. Thus, the requirement to take up the cross is addressed to those who followed him physically during his lifetime.

- Mark and Luke : every disciple

Marc

In Mark, the requirement applies to everyone, as is shown by the fact that Jesus addresses not only the disciples, but also the crowd of those who listen to him, and as v. 35 also shows that the motivation for accepting to lose one's life comes from the acceptance of the Gospel, and therefore refers to every Christian.

Luke

In Luke, the requirement also applies to anyone who wants to be a disciple of Jesus. Not only does he clearly use the word "all", but taking up his cross becomes a "daily" requirement, encompassing the various experiences of Christian life.

- What cross?

Let us recall the context of the first proclamation of the passion following Peter's confession of faith: thus, whoever wants to follow Jesus must be ready to go all the way. For Jesus and for anyone who wants to follow him, it is a matter of doing God's will. As "denying oneself", "taking up one's cross" and "losing one's life" are closely related, they must be interpreted in relation to each other.

- Denying oneself: the will of God must take precedence over one's own will.

- Losing one's life: shifting priorities in following Jesus can lead to death to oneself, renouncing one's most precious interests and attachments.

Thus, "to take up one's cross" refers to all that is implied by the requirement of accepting the will of God as expressed through the Gospel. Having said this, it should be noted that the expression does not refer to any form of trial, but only to what flows from the acceptance of the Gospel.

- Matthew: the Twelve

- One requirement among others?

- "He who does not take up his cross is not worthy of me" (Mk 10:38 ||)

(In the parallel texts that follow, words similar to the three pericopes are underlined, those that are unique to them are in italics, those that Matthew shares with Luke are in blue, and finally those that are similar in both Matthew texts are in red.)

Mt 16 Mt 10 Lc 14 37 Whoever loves father or mother more than me is not worthy of me; and whoever loves son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me; 26 "Whoever comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, yes, and even life itself, cannot be my disciple. 24 Then Jesus told his disciples, "If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. 38 and whoever does not take up the cross and follow me is not worthy of me. 27 Whoever does not carry the cross and follow me cannot be my disciple. 25 For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it. 39 Those who find their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it. The texts of Mt 10 and Lk 14 appear similar to what we saw earlier in Mark 8:34 and its parallel in Mt 16, yet they differ from it: not only do we now have a negative form (not... not) and no longer a positive one, but the context and meaning are different. These two texts proper to Matthew and Luke, and absent from Mark, no doubt come from a presynoptic tradition which had retained in a different form the words of Jesus about the need to take up his cross, and inserted them in the context of family relationships.

- Particularities of Matthew