|

Summary

Mark, followed by Matthew and Luke, marks the death of Jesus by rending the veil of the temple. After the feeling of having been abandoned, God intervenes to rehabilitate Jesus: the destruction of the temple is realized, for with the rending of the veil that separated the sacred from the profane, the presence of God has disappeared. Matthew accentuates the apocalyptic character of the scene by adding six other phenomena: the earthquake, the rocks splitting open, the tombs opening, the bodies of saints raising up, then going to Jerusalem and being visible there. Luke, for his part, does not associate the rending of the veil with the death of Jesus, but rather with the eclipse of the sun that takes place: nevertheless, he expresses the same anger of God. These three evangelists represent one stream of tradition around the veil of the sanctuary, for there is another, much more positive stream, represented by the epistle to the Hebrews, where Jesus passed through this sanctuary with his own blood to offer an eternal sacrifice in the holy place in heaven.

Matthew adds phenomena of his own, first of all four that appear in the form of a quatrain and which are interrelated and almost synonymous: the earth shakes, causing the rocks to rend, which causes the tombs to open and allows the dead to come out of them. This quatrain undoubtedly comes from popular circles, familiar with the Old Testament, for whom the arrival of God at the end of time is accompanied by cosmic phenomena. For Matthew, it is the death of Jesus that causes the raising of the saints fallen-asleep on the same Friday. But to reconcile these popular accounts with the tradition of the priority of Jesus' resurrection being seen on Sunday, Matthew adds two other phenomena where the raised saints go on Sunday to Jerusalem and will be visible there, bearing witness to the resurrection of Jesus; the addition of these two phenomena also allows Matthew to evoke Ezekiel 37 where God gives life to the dead bones, a sign that the last times have come.

- Translation

- Comment

- The Veil of the Sanctuary Was Rent (Mark 15: 38; Matthew 27: 51; Luke 23: 45b; Gospel of Peter 5: 20)

- The Role of This Phenomenon in the Gospel Narratives

- Mark

- Matthew

- Luke

- The Veil in Hebrews

- The Veils in the Temple of Jesus' Time

- Phenomena Marking Temple Destruction (Especially in Josephus and Jerome)

- Special Phenomena in Matthew 27: 51-53 (and GPet)

- The Four Terrestrial Phenomena in 27:51bc.52ab as Reactions to Jesus' Death

- The Descent into Hell

- Coming out of the Tombs, Entry into the Holy City, and Appearances (27: 53)

- Analysis

- The Evangelists' Theologies in Recounting the Rending of the Sanctuary Veil

- Matthew's Theology in Recounting the Special Phenomena

- Translation

Words of Mark shared by the other evangelists are underlined. In green words from Gospel of Peter found elsewhere..

| Mark 15 | Matthew 27 | Luke 23 | Gospel of Peter |

|---|

| | [(44 And it was already about the sixth hour, and darkness came over the whole earth until the ninth hour, 45a the sun having been eclipsed.)) | |

| 38 And the veil of the sanctuary was rent into two from top to bottom | 51 And behold, the veil of the sanctuary was rent from top to bottom into two. And the earth was shaken, and the rocks were rent, | 45b The veil of the sanctuary was rent in the middle (46 And having cried out with a loud cry, Jesus said, "Father, into your hands I place my spirit.")] | 5: 20 And at the same hour (midday) the veil of the Jerusalem sanctuary was torn into two.

6: 21 And then they drew out the nails from the hands of the Lord and placed him on the earth; and all the earth was shaken, and a great fear came about. 22 Then the sun shone, and it was found to be the ninth hour. |

| 52 and the tombs were opened, and many bodies of the fallen-asleep holy ones were raised. | | (Those present at Sunday dawn were hearing a voice from the heavens addressed to the gigantic figure of the Lord who has been led forth from the sepulcher)

10: 41 Have you made proclamation to the fallen-asleep?" 42 And an obeisance was heard from the cross, "Yes." |

| 53 And having come out from the tombs after his raising they entered into the holy city, and they were made visible to many. | | |

- Comment

Reactions to the death of Jesus fall into two groups, physical and external phenomena, and those of the people present on the scene. Let us first analyze the first group in two phases, first the rending of the veil of the sanctuary as told by Mark, Matthew, Luke and the apocryphal Gospel of Peter, and then the six phenomena specific to Matthew.

- The Veil of the Sanctuary Was Rent (Mark 15: 38; Matthew 27: 51; Luke 23: 45b; Gospel of Peter 5: 20)

| Marc | And the veil of the sanctuary was rent into two from top to bottom |

| Matthew | And behold, the veil of the sanctuary was rent from top to bottom into two |

| Luke | The veil of the sanctuary was rent in the middle |

| GPet | The veil of the Jerusalem sanctuary was torn into two |

- The Role of This Phenomenon in the Gospel Narratives

- Mark

- "Was rent" When there is a passive verb in the Gospels, the agent of action is usually God: it is God who rends (schizein) the veil. The only other time Mark uses the verb schizein is at the baptism of Jesus when God rends the heavens to allow the Spirit to descend upon Jesus (1:10). Thus, we are before an intervention of God that will conclude with the proclamation of the centurion: Truly, this man was a son of God. Now, at the cross, Jesus has just cried out to God: Why have you forsaken me? This is God's answer: by rending the veil of the sanctuary, thus condemning the holy place of the Jews, God is passing judgment on the chief priests and the Sanhedrin who condemned Jesus; it is a violent and angry act of God who wants to rehabilitate Jesus. While these chief priests tore (diarēgnynai) their clothes when they condemned Jesus, it is now God's time to rend the veil to condemn them.

So the theme of anger dominates this scene. But we could add the theme of sadness at the fate of Jesus. This is suggested by the story of Elisha rending his garment, inconsolable before the departure of Elijah, his master (2 Kings 2:12). In the same line, the Babylonian Talmud Mo‛ed Qaṭan 25b 25b proposes two sad events in which one should rend one's garment, the destruction of the temple and the destruction of Jerusalem.

- "the veil of the sanctuary". The role of this veil is to separate the sacred from the profane world. Therefore, to rend the veil is to destroy the sanctity of the place, and thus to destroy what makes it a sanctuary. The temple was seen as the dwelling place of God. The breaking of the veil and the disappearance of the holy character of the sanctuary means the disappearance of the presence of God, a little like a hermetic container which is pierced and lets out its rare gas. 2 Baruch (8:2), a Jewish apocryphal writing, tells that during the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans, an angel came and removed the veil and other accessories from the Holy of Holies, while a voice proclaimed: "Enemies and adversaries may enter, for he who kept the dwelling has left it".

For Mark's, the veil is rent in two, making it irreparable. In this way the sanctuary no longer exists. But there is more. This happens when darkness is all over the earth. It is therefore the proclamation that the day of the Lord has come, the sign that heralds the difficult days that await Jerusalem.

- Matthew

The apocalyptic and threatening character of the scene is accentuated in Matthew, for the rending of the veil of the sanctuary is accompanied by an earthquake and rending rocks; the reader of the evangelist recognizes the signs of the last days. On the other hand, the fact that the tombs are opening and the dead are raising is a positive sign. The divine judgment, therefore, begins with both positive and negative aspects.

- Luke

"The veil of the sanctuary was rent in the middle" It should be remembered that Luke, unlike Mark and Matthew, placed the rending of the veil before Jesus' death, so that this scene becomes more difficult to interpret: for if it is associated with the darkness that reigns, it has a negative character, underlining God's displeasure; on the other hand, if it is associated with the words of Jesus that follow ("Father, into your hands I place my spirit"), it has a positive character, because the opening of the veil allows Jesus to go to his Father. Let us consider both interpretations.

- The first interpretation associates the scene with the darkness that reigns. Why would Luke change the moment in Mark when the veil is rent by placing it before Jesus' death, when darkness reigns? When Jesus dies, Luke presents three groups of compassionate people, demonstrating the salvific side of this death, and in this positive context, the threatening nature of the rending veil could not fit. So he preferred to group them together with another threatening sign, the darkness over the whole earth. But there is more. Luke has a positive view of the temple: his Gospel begins in the temple with Zechariah (1:8), and ends in the temple where the disciples were constantly praising God (24:53), while his Acts mentions that Christians went to the temple every day to pray (Acts 2:46; 3:1). In the trial before the Sanhedrin there is no accusation that he threatened to destroy the temple (Luke moves this accusation to the trial of Stephen: Acts 6:14). Thus, by disassociating the rending of the veil of the sanctuary from the death of Jesus, Luke avoids desacralizing the Jewish temple at that time. It is rather a simple warning that, if one continues to reject Jesus, the destruction of the holy place will come, not just symbolic, but physical destruction.

- The second interpretation puts it in a positive context with the last words of Jesus. The Greek particle de should then be translated as "On the other hand, but", to express the contraction with the previous sentence about the darkness and the eclipse of the sun: after the negative, here is the positive. In this case, the rending of the veil leads Jesus to say that he entrusts himself to the Father. Let us not forget that the veil is not rent in two, but in the middle to open the passage, just as at Jesus' baptism heaven was opened to allow the Spirit to descend (3:21). Nor should we forget that Luke presents Jesus to us at the age of twelve in the temple when he says to his parents who are looking for him: "Did you not know that I must be in my Father's house?" If the temple is the Father's house, and Jesus now turns to the Father, is it not right that the veil should be opened in the middle to let him pass through?

As appealing as the second (positive) interpretation may be, it is nevertheless unlikely. The primary reason comes from the exact meaning of the words "to rend" (schizein) and "sanctuary" (naos). When Luke describes the scene of Jesus' baptism, he does not say that heaven is being rent as in Mark, but that it "opens". The verb "rending" always has a negative connotation for him (see 5:36: "No one rends a piece of a new garment to add it to an old garment; otherwise the new will be rent, and the piece taken from the new will not match the old"; Acts 14:4: "And the people of the city were rent. Some were for the Jews, others for the apostles"; Acts 23:7: "As soon as he had said this, a conflict arose between the Pharisees and Sadducees, and the congregation was rent"). Thus, the rending of the veil cannot be interpreted as an opening to let the passage through, and it must be concluded that Luke gives this action the same negative force it has in Mark. As for the word "sanctuary", Luke knows how to distinguish it well from the word "temple": only priests can enter the sanctuary, like the priest Zechariah, and he never presents Jesus in the guise of a priest; it would therefore be incongruous for him to make Jesus pass through the sanctuary where only priests can go, especially since the chief priests have never ceased to express their hostility towards him. It is therefore the first interpretation which is the most plausible, where the rending of the veil is associated with darkness and the eclipse of the sun, a negative indicator of God's wrath.

- The Veil in Hebrews

The biblical scholars, who opted for the second (positive) interpretation of the rending of the veil in Luke, were often influenced by the epistle to the Hebrews. Therefore, we must stop there for a few minutes.

- Even if we do not find in this epistle to the Hebrews the words naos (sanctuary), hieron (temple) or schizein (to rend), the word katapetasma (veil) nevertheless appears three times: :

- 6: 19-20 : "We have this hope, a sure and steadfast anchor of the soul, a hope that enters the inner sanctuary behind the veil, where Jesus, a forerunner on our behalf, has entered, having become a high priest forever according to the order of Melchizedek."

- 9: 2-3 : "For a tent was constructed, the first one, in which were the lampstand, the table, and the bread of the Presence; this is called the Holy Place. Behind the second veil was a tent called the Holy of Holies"

- 10: 19-20 : "We have confidence of entrance into the Holies in the blood of Jesus, an entrance which he inaugurated for us as a new and living way through the veil, i.e. his flesh"

The Epistle to the Hebrews assumes the following scenario: Once a year the Jewish high priest would cross the veil to enter the holy of holies where he would incense the golden lid (kappōret) of the Ark of the Covenant and sprinkle it with the blood of a bull and a goat that had just been sacrificed (see Leviticus 16:11-19). Thus Christ, the high priest, crossed the veil, which is his flesh, to enter into the holy of holies, which is the highest in heaven, using his own blood to complete the sacrifice begun on the cross, opening the way for all believers to enter in turn into the holy place of heaven.

- How can we explain this positive tradition around the veil with the negative one found in Mark? It can be assumed that very early in Christian reflection it was understood that the death of Jesus redefined the notion of God's presence among the chosen people, a presence that had been found until then in the veiled sanctuary of the Israelite liturgy. One strand of this reflection led to what we find in Mark, where Jesus' prophecy of the destruction of the temple combined with the crucifixion, seen as a rejection of his preaching on the reign of God, came to be symbolized by the irreparable rending of the veil that had hitherto expressed the presence of God. But another stream of this reflection has been directed rather towards a theology of Christ as the high priest of a new covenant, so that even though the sanctuary of Jerusalem has lost all meaning, God's presence continues, but in the heavenly sanctuary, and open to all believers who accept to follow Jesus through the veil. Thus, one current has led to a negative view of the veil, another to a positive one.

- The Veils in the Temple of Jesus' Time

- There has been much discussion among the biblical scholars about the veils of the temple, one identifying up to thirteen. Many of these studies are based on the Pentateuch, which describes the meeting tent in the desert, but a description colored by his experience of the temple of his time. The various editions of the temple are royal undertakings that are supported by going back to the prescriptions of Moses. This leads to anachronisms, for unlike the tent in the desert, the royal temples were certainly divided by gates, not veils. All this gives rise to incongruous situations, for example 1 Kings 6:31-34 speaks of gates, while the equivalent passage in 2 Chronicles 3:14 speaks of veils leading to the holy of holies. In short, the texts must be handled with caution.

- Let us consider the temple at the time of Jesus, whose renovations, still in progress, had been initiated by Herod the Great. At one end of the inner courtyard stood the sacred temple itself, which was divided into two rooms (see the detail at the bottom of the map on Jerusalem). The first opened with a portal and was called the Sacred Place (Hêkāl), and at the end of this room was another, smaller one called the Holy of Holies (Děbîr). The two veils of interest to us are that of the entrance to the Sacred Square, the outer veil, and that of the entrance to the Holy of Holies, the inner veil. There would also be a third veil, because in the tabernacle of the Holy of Holies there was like a veil delimiting the area.

- So, which of these veils do the synoptics refer to? If we refer to the Old Testament, the word katapetasma (veil) can designate the outer veil as well as the inner veil, but usually it refers rather to the inner veil, whereas the outer veil was called: kalymma. In terms of vocabulary, the Synoptics would therefore rather refer to the inner veil, as confirmed by the letter to the Hebrews. But some biblical scholars opted for the outer veil because the phenomenon had to be seen, especially by the centurion. Others also opted for the outer veil because, according to Josephus, the veil had four colours to symbolize the elements of the universe (fire, earth, air and water), and the rending of the veil had to have a cosmic dimension. In all this, we forget the fundamental question: what knowledge could the evangelists have of the different veils and their symbolism, they who probably never set foot in the temple, not to say in Jerusalem for some of them. More radically, what knowledge could the reader of the Gospels have of them? The evangelists could assume from their audience the knowledge of certain major themes of Scripture, but not much more. So the whole debate about the right veil is somewhat futile.

- Phenomena Marking Temple Destruction (Especially in Josephus and Jerome)

How did the story of the rending of the veil of the sanctuary fit the mentality of the people of the first century and how was it interpreted by the first Christians? It is immediately clear that for the people of that period it was normal that God (or gods) frequently intervened with extraordinary signs to mark the death of important figures. For example, when Herod the Great had the Jew Matthias put to death, who had stirred up a youth movement to purify the temple by removing the golden eagle, there would have been a moon eclipse that night (Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, 17.6.4: #167). Or, according to Cassius Dio (History 60.35.1, 2nd c.), there would have been various omens at the death of Emperor Claudius, such as a comet that could be observed for a long time, or the doors of the temple of Jupiter opening by themselves. Let us consider two important witnesses.

- Josephus (born in Jerusalem in 37/38 and died in Rome around 100)

The Jewish historian Josephus, in The Jewish War (6.5.3: #288-309), tells us of eight extraordinary events during the 60s to 70s which he considers to be God's warning signs of the destruction of the temple by the Romans in the year 70.

In the Heavens:

- "It was first when a sword-like star appeared over the city"

- It was also "a comet that persisted for a year"

- "At three o'clock in the night, a light shone on the altar and temple, bright enough to make it look like daylight, and it lasted half an hour."

- "So all over the country, before the sun sets, tanks and armed battalions spread out in the air, rushing through the clouds and surrounding the cities"

In the temple :

- "A cow brought by someone for the sacrifice gave birth to a lamb in the courtyard of the Temple "

- "One saw the door of the inner temple, facing the East, - though it was of brass and so massive that twenty men did not close it effortlessly at dusk... that opened by itself at midnight. "

- "At the feast of Pentecost, the priests who, according to their custom, had entered the Inner Temple at night for the service of worship, said that they had perceived a tremor and noise, and then heard these words as uttered by several voices: 'We are leaving from here'".

- A certain Jesus, the son of Ananias, whom the Jewish authorities had arrested, beaten and handed over to the Romans to be killed, and who was later released, began to cry out in the Temple for years: "Voice from the East, voice from the West, voice of the four winds, voice against Jerusalem and against the Temple, voice against the new spouses and new wives, voice against all the people!"

In such a context, it is easy to guess that the reader of the Gospels had no problem hearing or reading that the veil of the sanctuary was torn at the death of Jesus. For the Jews themselves saw signs of the destruction of the temple. Little attention is paid to whether the events took place in 30 AD, at the death of Jesus, or in 60 or 65 AD as with Josephus. Thus the Church historian, Eusebius of Caesarea (Chronicle), relates to the period of Jesus an eclipse reported by Phlegon, an earthquake in Bithynia, and the events recounted by Josephus at the Jewish Pentecost.

- Jerome (born in Stridon in 347 and died on 20 September 420 in Bethlehem).

Jerome played an important role in the development of the tradition of the veil, mixing the material of Josephus with that of apocryphal Christian writings. Let us consider the main references.

- Epistle 18a (Ad Damasum Papam 9): (Commentary of Isaiah 6:4 on his vision of the throne of God where the Seraphim sing of his holiness) "He (Isaiah) adds that 'the lintel (over the door frame) and the smoke that fills the whole house' are a prophetic figure of the destruction of the temple of the Jews and the burning of the city of Jerusalem, which we see today buried under its own ruins".

- Epistle 46 (Paulae and Eustochii ad Marcellam 4): Jerome associates the rending of the veil of the temple with the fact that Jerusalem is surrounded by an army and the departure of the angelic protection.

- Commentariorum In Evangelium Matthaei Libri Quattuor: Jerome refers to the Aramaic version of the Gospel used by the Nazoreans in the region of Berea or Aleppo, writing: "We read that the lintel of infinite size of the temple was smashed and fractured", and refers to the angels crying in the temple mentioned by Josephus.

- Epistle 120 (Ad Hedybiam 8): referring again to Josephus and the Gospel of Matthew, he writes: "It does not say that the veil of the temple was rent, but that the lintel of the great temple was heaved over".

- Commentarium in Isaiam 3: again commenting on Isaiah 6:4, he mentions that the lintel of the temple was heaved over and the hinges were broken, fulfilling the Lord's threat in Mt 23:38 that the house would be left deserted; according to him, this is a reference to the period when the Romans surrounded the city.

All this shows that Jewish tradition about the omens surrounding the destruction of the temple has infiltrated Christian understanding of the phenomena surrounding the death of Jesus. On both the Jewish and Christian sides these phenomena express God's anger, with those connected with the death of Jesus around 30 AD heralding the greatest destruction in 70 AD. But the distinction between the two groups has been eroded, so that the rending of the veil of the sanctuary, which had a symbolic function, became the shaking and lifting of the lintel of the temple which occurred when the Roman army destroyed the building. The catalyst for this merging of the two groups of phenomena was the Old Testament, like this passage from Isaiah 6:4 nentioned above.

- Special Phenomena in Matthew 27: 51-53 (and GPet)

The special phenomena following the rending of the temple are peculiar to Matthew and reflect in a very imaginative way an apocalyptic eschatology. Its structure can be presented as follows.

| 51a | And behold, the veil of the sanctuary was rent from top to bottom into two. |

| b | And the earth was shaken, |

| c | and the rocks were rent;, |

| 52a | and the tombs were opened, |

| b | and many bodies of the fallen-asleep holy ones were raised,. |

| 53a | And having come out from the tombs |

| b | after his raising |

| c | they entered into the holy city; |

| d | and they were made visible to many. |

Four lines have been underlined to show their similarity, all beginning with "and" and having a verb in the passive past tense (aorist in Greek), and differing from the more complex structure of verses 51a and 53. They offer the appearance of a poetic quatrain, probably from a pre-Matthean source. Verses 51b and 51c are synonymous, while verse 52 is a consequence of 51bc, i.e. the tombs open because the rocks rend. As for v. 53, it is a reflection on v. 52.

- The Four Terrestrial Phenomena in 27:51bc.52ab as Reactions to Jesus' Death

The four earthly phenomena are in addition to the two other signs mentioned: darkness on the earth and the rending of the veil of the sanctuary. But these six signs do not all have the same visibility. For example, the darkness on the earth and the earthquake are much more visible than the rending of the veil of the sanctuary. Matthew seems to recognize this fact, since it was when the centurion saw the earthquake that he was shaken (27:54). Thus, earthquake appears to be the dominant factor governing the other three phenomena. Although earthquakes are a frequent event in Palestine, for Matthew, in the passive form, it is clearly God who is the author. Let us look at each of the phenomena.

- And the earth was shaken (27, 51b)

In the Old Testament, there are many examples where the earthquake is a sign of God's judgment and the end of time (for example, Joel 2:10: "The earth quivers before him, the heavens tremble! The sun and the moon become darker, the stars lose their brightness!"; Psalm 77:19: "The voice of your thunder in its rolling. Your lightning illuminates the world, the earth shakes and trembles"). In the same way 1 Enoch 1:3-8: "The Holy One, the Great One, will leave His dwelling place, the God of eternity will come to earth...All will be terrified...All the ends of the earth will tremble, trembling and great fear will seize them to the ends of the earth. The high mountains will shake, fall, and collapse, the high hills will be lowered to the liquefaction of the mountains and melt like wax before the fire. The earth will open into a yawning abyss, everything on earth will perish, and judgment will come upon all things". Thus, Matthew's reader should easily recognize through the earthquake and the rending of the veil the sign of God's judgment. Even the Greco-Roman public knew, for example, Virgil, who had reported that the Alps had trembled at Caesar's death.

- and the rocks were rent (27, 51c)

Literally, the rocks were rent (schizein), as what happened for the veil of the sanctuary. Several passages in the Old Testament present the coming of God in the image of the splitting rocks: "And in that day His feet shall stand on the Mount of Olives over against Jerusalem on the east side. And the Mount of Olives shall cleave (schizein), half to the east and half to the sea", LXX Zechariah 14:4 (see also Isaiah 2:19; 1 Kings 19:11-12, Nah 1:5-6).

- the tombs were opened

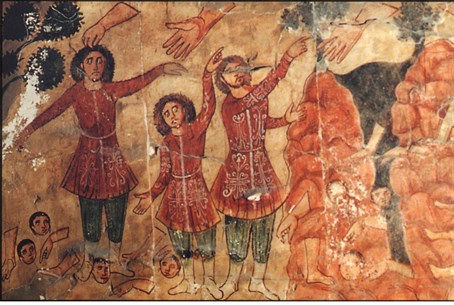

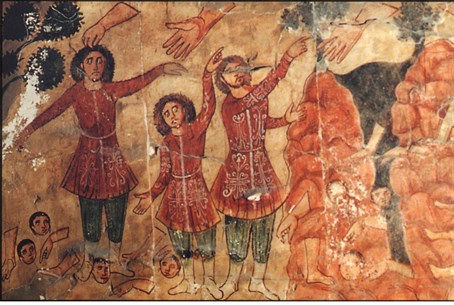

Mural painting of the synagogue of Dura Europos - Ezekiel 37

For Matthew, the act of opening the bowels of the earth after Jesus' death is included with the opening of heaven at the beginning of Jesus' ministry, at his baptism (3:16). The connection between the rocks that are rent and the opening of the tombs is beautifully illustrated by this mural found in the synagogue of Dura Europos (3rd c.), inspired by Ezekiel 37 where Yahweh gives life to bones. Two olive trees can be seen on each of the pieces of rock split in two, and the graves dug next to the mountain exposing the bodies of the dead and their limbs; a figure reaching out his hand, perhaps the Davidic messiah, brings them back to life. Ezekiel 37 certainly influenced Matthew in this scene, especially vv. 12-13: "Behold, I will open your graves; I will bring you up out of your graves, my people, and I will bring you back to the land of Israel. You will know that I am Yahweh when I open your graves and bring you up out of your graves, my people"

For Matthew, the act of opening the bowels of the earth after Jesus' death is included with the opening of heaven at the beginning of Jesus' ministry, at his baptism (3:16). The connection between the rocks that are rent and the opening of the tombs is beautifully illustrated by this mural found in the synagogue of Dura Europos (3rd c.), inspired by Ezekiel 37 where Yahweh gives life to bones. Two olive trees can be seen on each of the pieces of rock split in two, and the graves dug next to the mountain exposing the bodies of the dead and their limbs; a figure reaching out his hand, perhaps the Davidic messiah, brings them back to life. Ezekiel 37 certainly influenced Matthew in this scene, especially vv. 12-13: "Behold, I will open your graves; I will bring you up out of your graves, my people, and I will bring you back to the land of Israel. You will know that I am Yahweh when I open your graves and bring you up out of your graves, my people"

- many bodies of the fallen-asleep holy ones were raised

The adjective "asleep" is a euphemism for dead people. Who are these "saints" who are raising? For Matthew, they are Jews who have died as a result of a holy life, specifically those in Jerusalem, not far from the cross where Jesus died. Throughout the ages, attempts have been made to identify who were raising. All this is useless: we are faced with a popular and poetic description that remains deliberately vague. It should be noted that in Matthew there is no equivalent to a scene of identification of the raised, as in Luke or John, because the whole emphasis is on the power of God. Moreover, it is not the final manifestation of God's reign with the separation of the good from the wicked, but rather the anticipation of that final moment, the sign that the judgment has begun.

- The Descent into Hell

- The first Christians were asked: if Jesus died on a Friday and rose again on a Sunday, where was he in the meantime? We have seen that with Luke 23:43 there was no problem: Jesus rose from the dead on Friday, since he promises the compassionate wrongdoer to be with him that very day in paradise. This is how we must understand here the scene in Matthew where the sleeping saints are raised at the very moment Jesus dies: Friday is a moment of victory.

- But there was another view among the first Christians, where Jesus entered heaven only on the day of Passover, and in the meantime he descended into the underworld. This vision may have been influenced by the Jewish apocalypse and the notion of the Scheol where the dead were rotting in a semi-vegetative life in the depths of the earth: it was then important that the victorious Jesus should crush the evil spirits in chains from original sin (see 1 Enoch 10:12) and free all the saints from their prison. Some texts echo this vision.

- 1 Peter 3:19: "Then he (Christ) went out and preached even to the spirits in prison".

- 1 Peter 4:6: "For this cause the Good News was preached even to the dead, that they might be judged according to men in the flesh and live according to God in the spirit".

- Ephesians 4: 8-9: "Therefore it is said, 'Rising up on high, he has taken captives, he has given gifts to men. "He ascended," what does that mean, except that he also descended into the nether regions of the earth?"

- Very early in the second century, these two different visions would've become intertwined. This is reflected in the apocryphal Gospel of Peter who, on the one hand, knows the tradition reflected in Matthew where "the whole earth was shaken" (6:21), which caused the opening of the tombs, and who, on the other hand, writes that a voice spoke to the Lord saying, "Have you preached the news to those who sleep? And an answer was heard from the cross: 'Yes'", and this announcement could only have been made between the time of his death and his resurrection on Sunday. Some Christian authors go in the same direction, for example Justin (Dialogue 72:4), who writes that Christ made a proclamation of Jeremiah that the Lord God remembered the dead asleep in the earth and went there to preach the good news. That being said, there is no reason to believe that Matthew knew of this tradition of descent into hell.

- Coming out of the Tombs, Entry into the Holy City, and Appearances (27: 53)

This raising of the saints from the tombs poses a theological problem: if Jesus is the first-born of the dead (see 1 Cor 15:20; Col 1:18), and thus was able to lead the others out of death (1 Thess 4:14), how is it possible that all these dead are raised before even mentioning that Jesus has risen?

- "after his raising (egersis)" (27: 53b). The expression poses a problem, and a problem which is not easy to solve, because egersis appears only here in the whole New Testament. It can be given two meanings.

- "after his own raising": the emphasis would be on the possessive adjective "his."

- "after the raising of Jesus": a transitive action where we can imagine that it is God who raises him.

In both cases, the action takes place in the context of Easter. But there would also be a third possible meaning: "after his raising [from them]", i.e. all the sleeping saints; this interpretation has the advantage of keeping the link with what we have just been talking about, but represents a grammatical tour de force (with two name complements: the raising of him from them) that it would be imprudent to follow.

Let us now consider "after his (Jesus') raising" in the whole of v. 53. The majority of biblical scholars agree that v. 53 is to be seen in a paschal context. In this case, where should the punctuation be placed in this verse?

- On can put a comma after 53b, so that 53a and 53b form a whole: "having come out of the tombs after his raising (on or after Sunday), they entered the holy city..." In this case, even though the saints woke up on Friday, they waited in their tombs for Jesus to resurrect on Sunday (this is too much courtesy!).

- On can put the comma after 53a, so that 53b would be linked to 53c: "And when they came out of the tombs, after his raising they entered the holy city and were seen by many"; thus, even though the saints came out of their tombs on Friday, they were only visible on Sunday. This last option would be the preferable one, because it ensures the priority of the apparitions to Jesus, and the "after" becomes a causal preposition: the resurrection of Jesus made it possible for the raised saints to appear in Jerusalem.

- "The Holy City" (27, 53c). Our interpretation of Matthew implies that the raised had to spend a few days in a certain place, and now we must try to understand why he brings them into the holy city. First of all, what does he mean by "holy city"? Passages like Isaiah 48:2; 52:1; Revelation 11:2 and Matthew 4:5-6 refer all to Jerusalem, the "holy city". Some biblical scholars have seen it rather as a reference to the holy city of heaven, relying for example on apocryphal writings such as The Martyrdom (Ascension) of Isaiah (9:7-18). But this is forgetting that Matthew writes: "and were visible to many", which cannot be applied to heaven. It is indeed an entry into the earthly city of Jerusalem.

- "They were made visible to many" (27:53d). Usually, when we speak of resurrection, we speak of entrance into eternal life. And the fact that they were visible to a limited number of people is consistent with the accounts of the resurrected Jesus: "God raised him up on the third day and gave him to manifest himself, not to all the people, but to the witnesses whom God had chosen beforehand" (Acts 10:40-41). But the fact that nowhere else in the New Testament is there any reference to these raised people led a whole stream of early Christian communities to present a different way of understanding this phenomenon, presenting it not as resurrection, but as resuscitation, i.e., it would not be the entry into eternal life, but a return to ordinary life, so that all these people would have to die again; we would simply be faced with a miracle of healing as Jesus performed during his ministry. An example of this trend is represented by the Gospel of Nicodemus, an apocryphal scripture, which names Simeon and his two sons among those who awoke from their tomb and returned to live in Arimathea.

The problem with this interpretation of a simple resuscitation, and not a true resurrection into eternal life, is that it does not do justice to Matthew's presentation, which emphasizes the apocalyptic character of the event and associates it with a set of signs from heaven, typical of the end times. All these deaths, associated with the resurrection of Jesus, are entering the city where, for the Jews, God's judgment for all was to take place at the end of the world, and their appearance in this city is intended to testify that Jesus truly conquered death and to confirm the promise that all the saints will rise again. This is very different from the miracles of resuscitation during Jesus' ministry, where people who came back to life did not have to give such testimony. What happened to the raised after entering Jerusalem? Matthew does not say, just as he does not say anything about the resurrected Jesus after his last appearance (Mt 28:16-20).

- Analysis

The phenomena described by Matthew represent an interpretation, in the pictorial language of the apocalypse, of the meaning of Jesus' death. To ask the question of the literal historicity of all these phenomena is to fail to understand the nature of the symbols and the literary genre they represent. It is as if people in the year 4,000 discovering George Orwell's book 1984 were questioning the literal historicity of all the details of what it says, especially the criticism of the society of its time. Apocalyptic imagery offers a very effective medium for translating truths that defy the ordinary world.

- The Evangelists' Theologies in Recounting the Rending of the Sanctuary Veil

- The Synoptics narratives are based on Mark. The rending of the veil of the sanctuary at the end of the Gospel expresses God's anger at the refusal to recognize him as a beloved son; instead, a stranger, the centurion, will recognize him. The reader of Mark will have recognized the negative character of the scene: the sanctuary is no longer the place of God's presence, and in this sense Jesus' prediction to destroy the temple is fulfilled.

- Acknowledging that there was a tradition around the veil of the sanctuary, as we see in the epistle to the Hebrews, we must then admit that Mark did not create this tradition. The Hebrews saw it as a positive reality that Jesus went through this sanctuary with his own blood to offer an eternal sacrifice in the holy place in heaven, while Mark saw the destruction of the sanctuary as Jesus had predicted. With Luke, who has such a positive vision of the sanctuary, so that his Gospel starts in the sanctuary and ends there, it is the announcement of the future destruction of the temple, of that moment when the mountains will say, "Fall upon us" (Lk 23:30). Matthew adds a series of other apocalyptic phenomena.

- The apocryphal Gospel of Peter is a little different. First of all, it makes it clear that the darkness, which began at noon, ended at three o'clock in the afternoon (6:22). During these three hours, it describes in a very vivid way the difficulty for people to move around, the earthquake as soon as the body of the Lord was laid there. The body of Jesus, in dying, retains its divine power, for not only does the earth shake, but his body reaches gigantic proportions.

- Matthew's Theology in Recounting the Special Phenomena

- Matthew inherited from Mark two eschatological phenomena: darkness at noon and the rending of the veil, a sign of God's judgment at the death of Jesus. To these two phenomena, Matthew adds six: first, the poetic quatrain of 27:51b-52, a dramatic way for ordinary people, familiar with the Old Testament, to see the coming of the Lord's day, both negatively (earthquake, the rocks rending apart) and positively (the tombs opening and the bodies of the saints awakening), then the two phenomena that are a reflection on the raising of the saints (the entry into Jerusalem and the appearance to many). Matthew did not create this quatrain, which perhaps came to him from the same popular circles that gave him certain scenes from the infancy narratives (the Magi, the star of Bethlehem, the evil king) and the death of Judas. Since these scenes take place around Jerusalem, one can think that they were born in the Christian circles of Jerusalem.

- The last two phenomena around the arrival of the bodies of the saints in Jerusalem, we have said, come from the pen of Matthew. Under the pressure of tradition, Matthew had to connect the accounts of popular circles with the tradition of the priority of the resurrection of Jesus: even if the saints were raised on Friday, it was only on Sunday that this phenomenon could be seen in Jerusalem. These two additions of Matthew teach us two things. First of all, we must not fall into the trap of taking eschatological signs as historical events. Secondly, Matthew wanted us to see the connection between this scene and Ezekiel 37, where bones are presented in a pictorial way and come to life again: "Behold, I will open your graves, and I will bring you up out of your graves, my people, and I will bring you back to the land of Israel. You will know that I am Yahweh" (12-13). With the death of Jesus, the prophecy of Ezekiel is fulfilled; it is the beginning of the last days and the judgment of God.

|

Next chapter: Jesus Crucified, Part Four: Happenings after Jesus' Death: b. Reactions of Those Present

List of chapters

|

For Matthew, the act of opening the bowels of the earth after Jesus' death is included with the opening of heaven at the beginning of Jesus' ministry, at his baptism (3:16). The connection between the rocks that are rent and the opening of the tombs is beautifully illustrated by this mural found in the synagogue of Dura Europos (3rd c.), inspired by Ezekiel 37 where Yahweh gives life to bones. Two olive trees can be seen on each of the pieces of rock split in two, and the graves dug next to the mountain exposing the bodies of the dead and their limbs; a figure reaching out his hand, perhaps the Davidic messiah, brings them back to life. Ezekiel 37 certainly influenced Matthew in this scene, especially vv. 12-13: "Behold, I will open your graves; I will bring you up out of your graves, my people, and I will bring you back to the land of Israel. You will know that I am Yahweh when I open your graves and bring you up out of your graves, my people"

For Matthew, the act of opening the bowels of the earth after Jesus' death is included with the opening of heaven at the beginning of Jesus' ministry, at his baptism (3:16). The connection between the rocks that are rent and the opening of the tombs is beautifully illustrated by this mural found in the synagogue of Dura Europos (3rd c.), inspired by Ezekiel 37 where Yahweh gives life to bones. Two olive trees can be seen on each of the pieces of rock split in two, and the graves dug next to the mountain exposing the bodies of the dead and their limbs; a figure reaching out his hand, perhaps the Davidic messiah, brings them back to life. Ezekiel 37 certainly influenced Matthew in this scene, especially vv. 12-13: "Behold, I will open your graves; I will bring you up out of your graves, my people, and I will bring you back to the land of Israel. You will know that I am Yahweh when I open your graves and bring you up out of your graves, my people"